Passenger liner collision and sinking in the North Atlantic. Structured brief covering key facts, timeline, technical context, lifeboat reality, wireless/Californian controversy, investigations, and the safety legacy that led to SOLAS, lifeboat rules, 24-hour radio watch, and ice patrols.

Passenger linerNorth AtlanticMajor accidentSOLAS legacy

On this page

- Key facts

- What happened

- Ship & systems that mattered

- Timeline

- Why the loss was so large

- Aftermath, inquiries & liability

- Safety legacy (SOLAS, ice patrol, radio)

- Wreck discovery & deterioration

- Official sources

Key facts

At a glance

Vessel: RMS Titanic (White Star Line), Olympic-class ocean liner

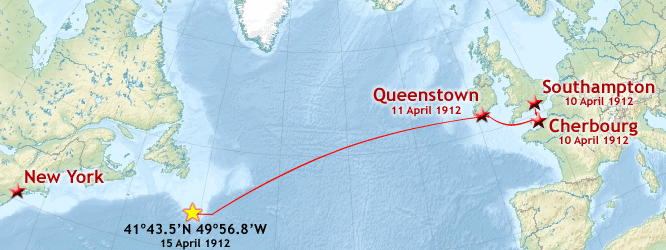

Route: Southampton → Cherbourg → Queenstown → New York (maiden voyage)

Collision: 14 April 1912, 23:40 (ship’s time), iceberg sighted 23:40; impact at ~23:40

Foundered: 15 April 1912, ~02:20

Location: North Atlantic (Grand Banks region / shipping lanes vicinity)

Deaths: ~1,500 (estimates vary)

People aboard: ~2,224 (often-cited estimate)

Survivors: ~705–708 (commonly cited)

Technical / operational headlines

High speed into an ice-reported area; lookouts sight iceberg too late for avoidance; progressive flooding across multiple compartments; lifeboat capacity and loading practice insufficient; evacuation training and command clarity weak; distress response delayed; survival in −2 °C water measured in minutes.

The post-loss regime shift: lifeboat space for all, drills, 24-hour radio watch, standardized distress rockets, and the International Ice Patrol — consolidated under the international safety framework that becomes SOLAS.

What happened

RMS Titanic, a British ocean liner operated by White Star Line, sank in the early hours of 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York (via Cherbourg and Queenstown). Of roughly 2,224 people aboard, about 1,500 died (estimates vary), making it one of the deadliest peacetime sinkings of a single ship.

At 23:40 on 14 April, the iceberg was sighted ahead. A rapid avoidance manoeuvre was ordered, but the starboard side struck, opening the ship to progressive flooding. Within about 2 hours and 40 minutes, the vessel broke and foundered. Many deaths occurred not from impact but from exposure in freezing water (~−2 °C).

The casualty scale was driven by limited lifeboat accommodation relative to persons aboard, boats launched under-filled, uneven access for Third Class, and the time lag before rescue ships arrived. The disaster became a forcing function for international maritime safety reform — notably SOLAS, lifeboat rules, radio watch, and ice patrols.

Ship & systems that mattered

Dimensions & layout

Titanic was ~882 ft 9 in (269.06 m) long with a maximum breadth of ~92 ft 6 in (28.19 m). She was the second Olympic-class liner built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast (Olympic first, Britannic last). Ten decks (excluding the officers’ quarters) — eight for passenger use — with class segregation embedded in the layout.

The “floating hotel” concept was explicit in the First Class spaces (Grand Staircase, lounges, restaurants), while Third Class — though better than many contemporaries — remained physically separated, affecting flow and access during emergencies.

Watertight subdivision & doors

The hull was subdivided into 16 primary compartments with 15 bulkheads; 11 vertically-closing watertight doors on the orlop deck could be closed from the bridge and locally. This contributed to the “practically unsinkable” reputation — but the design reality was that the ship could not survive more than a limited number of adjacent compartment breaches without progressive flooding.

The collision produced multiple thin gashes and seam separations below the waterline rather than one long single “rip”, enabling water ingress across several compartments and exceeding survivability margins.

Propulsion & power

Propulsion: two four-cylinder triple-expansion reciprocating steam engines plus a low-pressure Parsons turbine driving three propellers. Steam from 29 coal-fired boilers (159 furnaces). Coal consumption could exceed ~600 tonnes/day with ~176 firemen working in shifts.

Electrical plant: four ~400 kW steam-driven generators plus auxiliary sets. The stern-located electrical plant remained operational until late in the sinking, after which lights failed as water and breaker trips progressed.

Wireless (Marconi) capability

The Marconi wireless set (call sign MGY) ran 24-hour operations for passenger traffic (“marconigrams”) and navigation messages (weather/ice warnings). The radio room sat on the Boat Deck in the officers’ quarters; a “Silent Room” housed loud transmitter equipment.

During the casualty sequence, distress signalling included wireless (CQD and SOS), rockets, and lamp. Rescue timing, radio watch, and the Californian controversy became central to inquiries and later reforms.

Timeline

31 Mar 1909

Keel laid (Belfast, Harland & Wolff).

31 May 1911

Launched.

2 Apr 1912

Sea trials (Belfast Lough / Irish Sea). Crash-stop and handling trials; declared seaworthy.

10 Apr 1912

Departed Southampton (maiden voyage). Near-miss with SS New York due to displacement effects and snapped mooring lines.

10 Apr 1912

Cherbourg stop via tenders; additional passengers embarked. Departed for Queenstown.

11 Apr 1912

Queenstown (Cobh) stop via tenders; additional passengers embarked. Final departure ~13:30.

14 Apr 1912 (day)

Multiple ice warnings received from other ships; ship maintained near service speed (practice of the era).

14 Apr 1912 23:40

Iceberg sighted; avoidance ordered; starboard side impact produces multiple breaches below waterline.

15 Apr 1912 00:45

Distress calls transmitted (CQD then SOS) plus rockets; evacuation begins with “women and children first”.

15 Apr 1912 ~02:10

Last wireless transmission; flooding accelerates as deck edge submerges; power fails soon after.

15 Apr 1912 ~02:20

Ship breaks and founders; survivors in water face rapid cold incapacitation (~−2 °C).

15 Apr 1912 ~04:10

RMS Carpathia begins recovering survivors; arrival after sinking but before total exposure losses in boats.

18 Apr 1912

Carpathia docks New York; casualty lists evolve over days amid public pressure and grief.

1 Sep 1985

Wreck located by Franco-American expedition (Ballard / IFREMER); confirmed split bow/stern.

Why the loss was so large

Lifeboat reality vs persons aboard

Titanic carried 20 lifeboats (14 standard, 4 collapsible, 2 cutters) with an aggregate capacity of ~1,178 people — roughly half of the estimated persons aboard (~2,224) and far below the ship’s maximum passenger+crew capacity. This complied with (and exceeded) Board of Trade requirements for the era, which were outdated by ship size evolution.

Operationally, the average boat launched about ~60% full, wasting scarce capacity. Evacuation competence was impaired by limited drills, inconsistent boat loading practice, and uncertainty about safe boat occupancy.

Access, command, and class segregation under stress

Confusion was reported: a general alarm was not consistently understood; passengers were not uniformly briefed; and a scheduled lifeboat drill had not been held. Third Class passengers were physically separated and, in practice, many were delayed below decks.

The “women and children first” protocol increased survival differentials by sex and class. The Board of Trade figures commonly cited show First Class women survived at very high rates, while Third Class men and children suffered high loss rates.

Speed, lookout limits, and ice warnings

Titanic received multiple ice warnings but maintained high speed — consistent with prevailing practice and confidence in modern ships. The inquiries criticized maintaining “extremely high speed” following repeated warnings, even while noting it aligned with custom.

In calm, very cold night conditions, iceberg detection depended on lookout sighting and immediate bridge response. Once the berg was sighted at close range, the manoeuvre window was too small for a full avoidance.

Survivability after foundering: −2 °C water

The water temperature near the sinking was around −2 °C. Cold shock, rapid loss of motor function, and hypothermia made survival time in open water very short. Only a handful were recovered from the water; most survivors were in lifeboats.

This is why rescue timing mattered: even “fast” response by a distant ship could only save those who made it into boats, not the bulk who entered the sea after the final plunge.

Engineering note

Titanic’s reputation rested on subdivision and doors, but the design survivability margin is discrete: once enough adjacent compartments are open to the sea, progressive flooding overtops bulkheads and becomes a certainty rather than a probability. The “unsinkable” narrative was never a physics guarantee — it was a marketing simplification of a limited damage-stability envelope.

Aftermath, inquiries & liability

The news cycle was chaotic: early press reports incorrectly suggested the ship was being towed. Once confirmed, crowds formed at White Star offices across major cities; the human impact was especially severe in Southampton, where a large share of the crew originated.

Two major investigations followed: the U.S. Senate inquiry (April–May 1912, chaired by Sen. William Alden Smith) and the British Board of Trade / Wreck Commissioner inquiry (May–July 1912, presided by Lord Mersey). Both concluded lifeboat regulations were inadequate and criticized maintaining high speed into an ice-reported region.

U.S. Senate inquiry (themes)

Focused on operational practices, including speed after ice warnings, evacuation disorder and lack of drills, and especially the SS Californian’s proximity/response. The committee faulted regulatory laxity and argued Californian’s failure to respond to distress rockets violated “humanity” and law.

British inquiry (themes)

Concluded collision with iceberg was caused by excessive speed in the ice region, but held Captain Smith followed common practice (while emphasizing that future repetition could be negligence). The inquiry sharply criticized Captain Lord / Californian for failing to take sufficient action after observing rockets.

Liability & settlements (high level)

Claims and lawsuits followed in the U.S. and Britain. White Star pursued limitation of liability under U.S. law; the Supreme Court ultimately supported limitation, and settlements were markedly smaller than initial claimed totals.

Recovery & burial

Canadian ships (notably CS Mackay-Bennett) recovered hundreds of bodies; many were buried at sea due to embalming limits. Halifax became a major identification and burial center; Fairview Lawn Cemetery holds the largest group of Titanic burials.

Safety legacy (SOLAS, lifeboats, ice patrol, radio)

Titanic drove a permanent re-baseline of maritime safety: lifeboat space for every person embarked, mandatory lifeboat drills, inspections, and harmonized international standards via the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS).

The Radio Act of 1912 and SOLAS-linked measures reinforced continuous radio watch with backup power, and clarified that rockets at sea must be treated as distress unless explicitly identified otherwise. International Ice Patrol was created to monitor and report iceberg hazards in the North Atlantic shipping lanes.

What changed (practical)

Lifeboats: not a “minimum by tonnage” loophole, but capacity for all aboard; drills per voyage; improved launching procedures. Wireless: 24-hour watch and redundancy to prevent missed distress calls.

Why it matters now

Titanic is still used as the cautionary case for assumptions embedded in regulation: if a rule measures the wrong proxy (e.g., tonnage), the system will comply while safety silently degrades. It’s a template for how “normal practice” can become institutional risk.

Wreck discovery & deterioration

Discovery & layout on seabed

Located 1 September 1985 by a Franco-American expedition led by Robert Ballard with IFREMER support. The wreck lies ~12,500 ft (3,810 m) deep. The ship rests in two main pieces (bow and stern) separated by a debris field; the bow is more intact, the stern heavily collapsed from structural damage and seabed impact.

Rusticles and decay

Rusticles — iron-eating microbial formations — are consuming the wreck. Later expeditions documented substantial deterioration, with notable features disappearing over time (e.g., significant losses reported by 2019).

Material discussions

Post-discovery investigations challenged early myths of a single long gash, instead indicating multiple breaches and seam separation. Subsequent analysis and archival review also prompted debate on steel brittleness in cold conditions and rivet quality by standards of the era.

Official sources

Authority sources (keep short)

Use official inquiries, regulators, and primary institutional records. Add secondary analysis only if needed. ExpandCollapseCopy bibliography British Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry (Lord Mersey) Inquiry

Official UK inquiry (May–July 1912). Add your chosen archive link. Link (placeholder)

UK Board of Trade / Wreck Commissioner. (1912). Report of the formal investigation into the loss of RMS Titanic (Lord Mersey). U.S. Senate Inquiry (Sen. William Alden Smith) Inquiry

U.S. Senate hearings and findings (April–May 1912). Add your chosen archive link. Link (placeholder)

United States Senate. (1912). Investigation of the sinking of the RMS Titanic (Senate hearings and report). SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) Convention Regulation

International convention establishing lifeboat capacity, drills, and other requirements. Use IMO or national archive source. Link (placeholder)

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). Initial adoption 1914; later revisions thereafter. International Ice Patrol (USCG) Safety

Ice monitoring and reporting program established post-Titanic to protect shipping lanes. Link (placeholder)

International Ice Patrol (U.S. Coast Guard). Iceberg monitoring and hazard reporting for North Atlantic shipping lanes. Radio Act of 1912 (U.S.) Regulation

Reinforced continuous radio watch and operational expectations for distress traffic after Titanic. Link (placeholder)

United States. (1912). Radio Act of 1912. Requirements for shipboard radio operation and monitoring.

RMS Titanic

Passenger liner disaster

| Date | 14–15 April 1912 |

|---|---|

| Type | Passenger liner |

| Location | North Atlantic |

| Operator | White Star Line |

| Fatalities | ~1,500 (est.) |

| Survivors | ~705–708 |

| Lifeboats | 20 boats (~1,178 capacity), often launched ~60% full |

| Water temp | ~−2 °C |

Legacy

SOLAS • lifeboat space for all • 24-hour radio watch • International Ice Patrol