ENGINE ROOM → Control & Operations

System Group: Control & Operations

Primary Role: Convert risk into repeatable, auditable actions under the SMS

Interfaces: Bridge team · Deck dept · PMS · PTW/RA · Class/Flag · MARPOL records · Makers manuals · Drills/Training

Operational Criticality: Absolute

Failure Consequence: Injury, blackout, pollution event, detention, prosecution, or a “routine job” becoming a casualty

SOPs are not paperwork.

They are the ship’s memory, discipline, and legal defence—written down.

They exist because the engine department is asked to do impossible things at the same time: keep the plant reliable, keep people safe, keep the ship compliant, and keep operations moving—often with fatigue, time pressure, and changing equipment.

1. Introduction

1.1 The value of procedures

Strict adherence to established procedures and recognised best practice in engine rooms is not optional. It is how ships avoid repeating the same failures: fires from fuel mist, injuries from uncontrolled energy, pollution from “routine” transfers, and blackouts caused by poor sequencing.

SOPs convert experience into a standard method that survives crew change, fatigue, and pressure.

1.2 Changes in the engine room

Modern machinery spaces carry new hazards that older “traditional” procedures do not fully cover: new fuels, EGCS, BWMS, hybrid power, high-voltage networks, integrated automation, and increasing cyber exposure. The plant is more interconnected than it looks, meaning one incorrect action can cascade faster.

This is why “zero tolerance” language has crept into modern SMS culture: not as a slogan, but because the margin for error has tightened.

1.3 An effective engineering team

SOPs are only as effective as the team executing them. The engineering department must run command and control: clear authority, clear communication, proper handovers, challenge culture, and disciplined supervision.

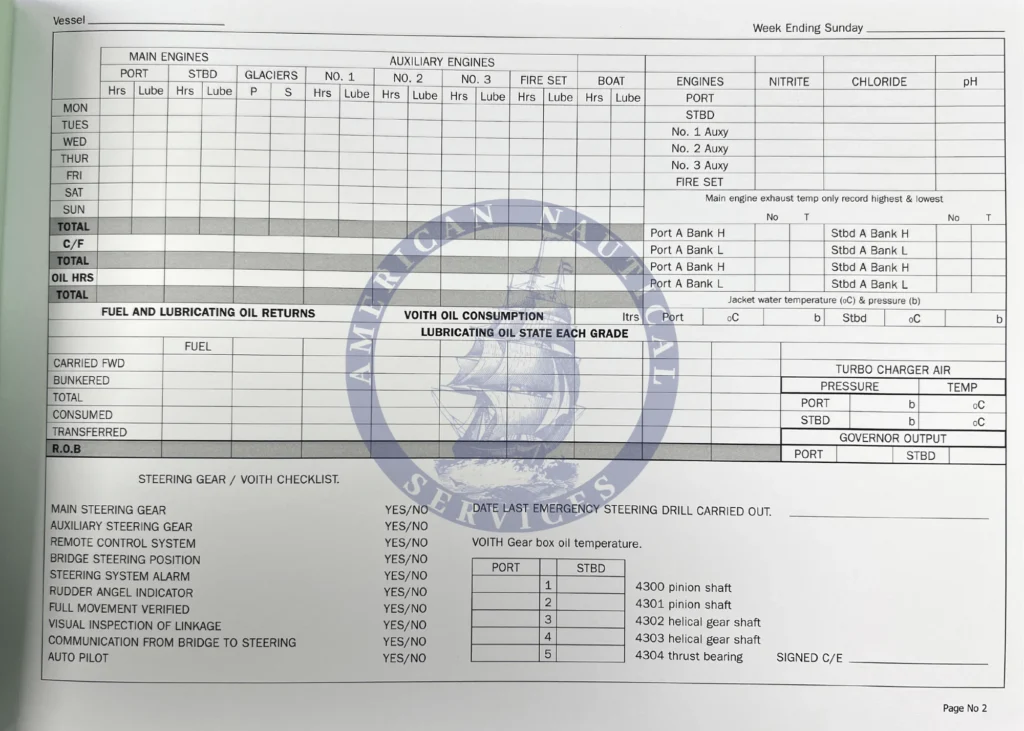

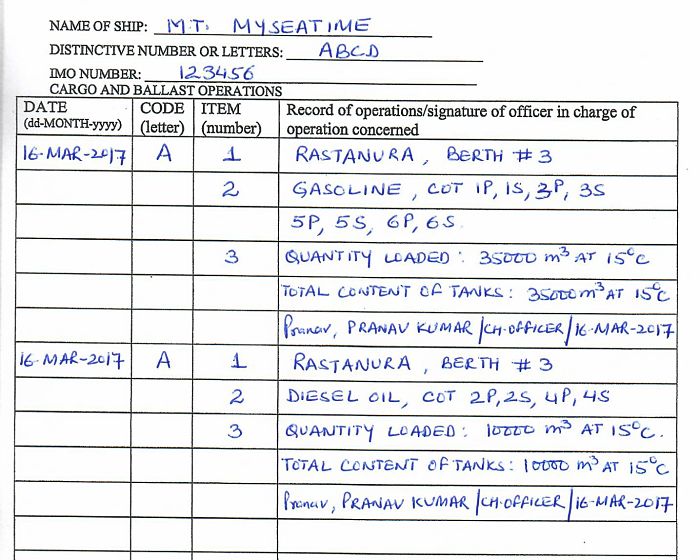

1.4 Documentation

Documentation is not admin overhead. It proves that the ship operated within the SMS and regulatory framework. When something goes wrong, records become evidence. Poor records are interpreted as poor control.

1.5 Environmental protection

Every member of the engineering team is a pollution-prevention operator, whether they like it or not. MARPOL compliance is procedural, not “good intentions”.

2. Where SOPs Live in the SMS

The ISM Code requires an SMS that is practical and ship-usable. In reality, SOPs usually sit in five layers:

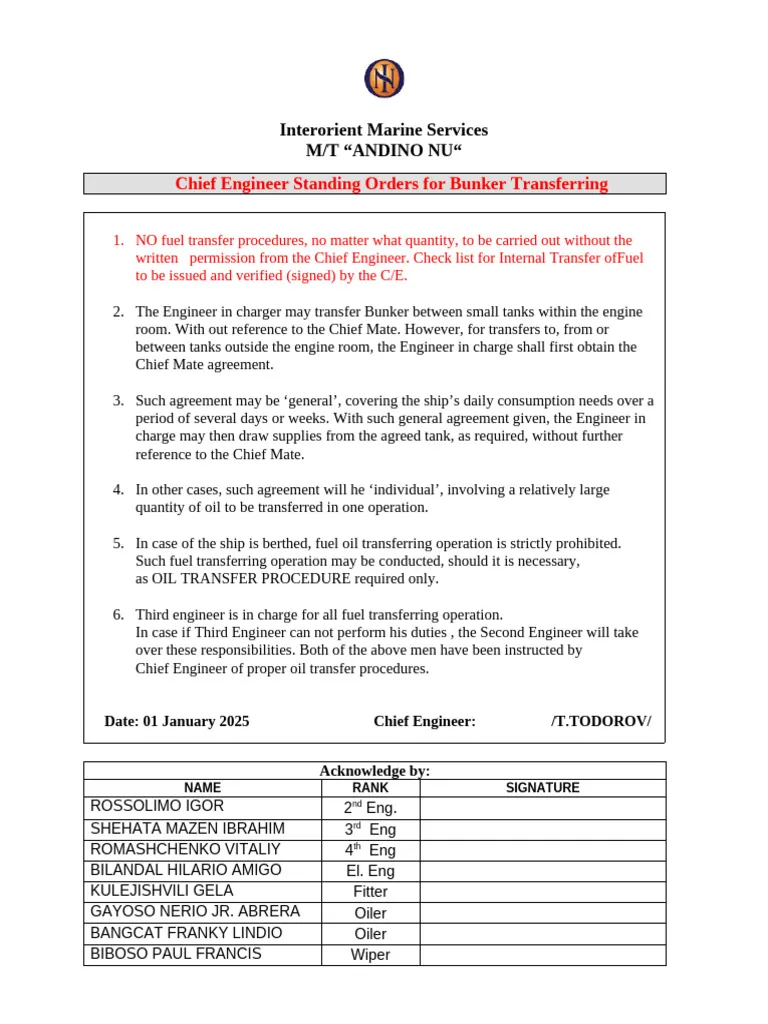

- Policy / Standing Orders (Master + C/E intent)

- Procedures (how we do the operation)

- Checklists (don’t forget steps under pressure)

- Risk Assessment + Permit to Work (control non-routine hazards)

- Records / Logs / Forms (proof it happened correctly)

The KISS principle matters: if procedures are too long to use during real operations, crews will improvise. The system then fails exactly when needed most.

The acronym KISS stands for “Keep It Simple, Stupid” (or sometimes “Keep It Short and Simple” or “Keep It Simple and Straightforward”). is a design and business principle which advocates that most systems work best if they are kept simple rather than made overly complicated.

The underlying principle is to prioritize clarity, functionality, and efficiency by avoiding unnecessary complexity in processes, designs, or explanations.

3. SOP Categories in the Engine Department

You’re right: this is a huge section. The clean way to make it usable is to classify SOPs into families—then list typical SOPs in each family, with notes on what makes them “critical”.

3.1 Watchkeeping SOPs

These procedures exist to prevent slow drift into failure.

Typical SOPs

- Taking the watch / relieving the watch (handover protocol)

- Rounds and inspections (E/R + steering gear room)

- Parameter monitoring and trend checks (temps/pressures/vibration)

- UMS routines (dead man alarm, call-out rules, alarm response)

- Engine room logbook entry discipline (what gets written, when, and why)

- Closed-loop communications with bridge (especially manoeuvring and incidents)

Operational reality

A watchkeeper doesn’t “monitor systems”. They monitor deviation: what has changed since last hour, last day, last voyage, last overhaul. A stable plant is one where small deviations are caught early.

Relieving EOOW — 12-Point Handover (Engine Watch)

- Plant Status Snapshot (what’s running, what’s stopped, what’s in standby)

Main propulsion mode (bridge/ECR/local), DGs online/standby, boilers (firing/standby), key auxiliaries, UMS status. - Orders & Operating Mode

Current bridge orders, expected manoeuvres, ETAs, speed/propulsion limitations, changeover requirements (ECA/SECA, fuel mode, shaft gen/PTO/PTH if fitted). - Power Management & Electrical Configuration

Bus configuration (split/parallel), PMS mode, load %, reserve margin, large consumers running/expected, any restrictions (e.g., one DG unavailable). - Alarms, Inhibits, Overrides, Bypasses

Any inhibited alarms, overridden trips, bypassed interlocks, test modes, isolated sensors—what, why, since when, and who authorised. - Machinery Condition & Trends

Any abnormal trends: temps/pressures, vibration, bearing temps, exhaust temps, scavenge/TC behaviour, lube oil quality indicators—what changed since last watch. - Leaks, Defects, Temporary Repairs

Active defects, leak watch, clamps/soft patches, temporary hoses, known weak points, isolation status, spill risks and containment readiness. - Work in Progress (permits + hazards)

All maintenance jobs ongoing or planned during the next watch: PTW/RA numbers, isolations applied, boundaries, people in spaces, “do not operate” equipment. - Isolation & Valve Line-Up Control

Any locked/closed valves, blanked lines, tagged breakers, LOTO key status, critical line-ups (bilge/ballast, FO/LO, cooling, steam) and “don’t touch” valves. - Tank Status & Transfer Intentions

Fuel service/settling/storage levels, sludge/bilge holding capacity, fresh water tanks, ballast condition (if engine controls involved), any planned transfers or restrictions. - Environmental Compliance Status

OWS readiness (operable/spares), any bilge restrictions, ORB entries in progress, discharge limitations (port/area rules), incinerator status (if used). - Safety Systems Readiness

Fire main pressure/line-up, emergency fire pump readiness, emergency generator status, CO₂ system status & any locks/seals, critical alarms tested/overdue. - Crew / Support Situation & Communications

Who is on watch with you, who is on call, contractors onboard, language/closed-loop expectations, key contacts (bridge, duty officer, chief), any expected call-outs.

Handover Close-out (required):

Both sign/initial watch log (or electronic handover) with time.

Relieving EOOW confirms understanding (closed-loop): “I understand: X inhibited alarms, Y isolation, Z planned transfer.”

3.2 Critical Operations SOPs

These are the ones that most often end in casualties or detentions when done casually.

Typical SOPs

- Pre-arrival / pre-departure engine readiness

- Manoeuvring support and bridge interface procedures

- Changeover of fuel (ECA/SECA, distillate/HSFO, dual-fuel transitions)

- Bunkering (including LNG / biofuels / additives where applicable)

- Starting / paralleling generators, PMS mode changes, split bus operations

- Boiler lighting-up, steam system pressurisation, thermal oil system operation

- Cargo-related machinery support (if applicable): cargo pumps, vapour systems, reliquefaction support interfaces

- Steering gear testing and emergency steering drills

- Critical transfers: bilge, sludge, waste streams, internal tank-to-tank movements

Core rule

“Critical” means: one mistake can escalate faster than you can reverse it.

Pre-Departure Checklist

Engine + Steering + Power + Alarms

Timing: Conducted before departure briefing, then re-verified immediately prior to “Stand-by Engines”.

Responsibility: EOOW (execution), Chief Engineer (verification), Bridge informed of any limitation.

1. Main Engine & Propulsion System

Mechanical & Fluid Readiness

- LO sump level correct, purifier running / ready, temperature within limits

- LO pressure normal on pre-lube, alarms clear

- Jacket water / HT–LT systems filled, vented, circulation confirmed

- Piston cooling oil / water system normal (where fitted)

- Fuel system lined up correctly for departure fuel (MGO / HFO / LNG etc.)

- Fuel temperature, viscosity, pressure stable

- Changeover completed and verified (SECA / ECA compliance if applicable)

Starting & Control

- Turning gear disengaged, interlock cleared, indicator verified

- Starting air pressure adequate, drains blown through

- Remote control tested (bridge → ECR → local, as applicable)

- Ahead / astern response tested at dead slow where permitted

- Emergency stop tested as per SMS (local confirmation only, no blackout)

Shafting & Propulsion

- Stern tube LO header level normal

- Shaft bearings temperature normal

- CPP system (if fitted): oil pressure, pitch feedback, control tested

- Shaft generator / PTO/PTH mode confirmed (in or out as required)

2. Steering Gear (Primary & Emergency)

This is a critical sail-away item. No shortcuts.

Primary Steering

- Both steering motors tested (Pump 1 / Pump 2)

- Changeover tested (auto/manual as applicable)

- Helm order vs rudder angle confirmed (port / stbd)

- Follow-up and non-follow-up modes tested

- Alarms tested and clear (low pressure, pump failure, power loss)

Emergency Steering

- Emergency steering power available

- Local/emergency control tested and reported to bridge

- Communication method verified (sound-powered phone / portable radio)

- Emergency steering procedure reviewed with assigned personnel

3. Electrical Power & PMS

Generators & Distribution

- Required DGs running for manoeuvring load (minimum redundancy met)

- Standby generator available and auto-start tested (blackout recovery)

- Bus configuration correct (split/parallel as required)

- Load sharing stable, no hunting

- Voltage / frequency within limits

Power Management System (PMS)

- PMS mode set correctly (Harbour / Manoeuvring / Sea)

- Large consumers identified and sequenced (thrusters, winches, pumps)

- Non-essential loads identified and ready for shedding

- Emergency generator auto-start logic armed and healthy

Emergency Power

- Emergency generator ready (fuel, cooling, starting)

- Emergency switchboard healthy

- Transitional power (UPS / batteries) healthy and alarm-free

4. Alarms, Safety & Automation Systems

Alarm Monitoring System (AMS)

- No standing critical alarms

- Any inhibited alarms listed, justified, authorised, time-limited

- Bridge alarm repeater healthy

Fire & Safety Systems

- Fire detection system healthy (no faults / disabled zones)

- Fire pumps ready (main + emergency)

- CO₂ / fixed firefighting system secured, no inadvertent release risk

- EEBDs, fireman’s outfit readiness confirmed (status check)

Bilge & Flooding Protection

- Bilge levels normal, alarms tested

- Bilge valves correctly lined up

- OWS isolated for manoeuvring unless permitted

Control & Automation

- IAS / PLC systems normal, no watchdog or comms faults

- Dead-man alarm tested (UMS vessels)

- Data logging and engine log active

5. Final Readiness & Communications

- All maintenance stopped or made safe

- All PTWs closed or clearly controlled

- Engine room secured for sea (tools, loose items, spills)

- Bridge informed:

- propulsion status

- steering tested

- power configuration

- any limitations or abnormal conditions

- EOOW confirms: “Engine room ready for departure.”

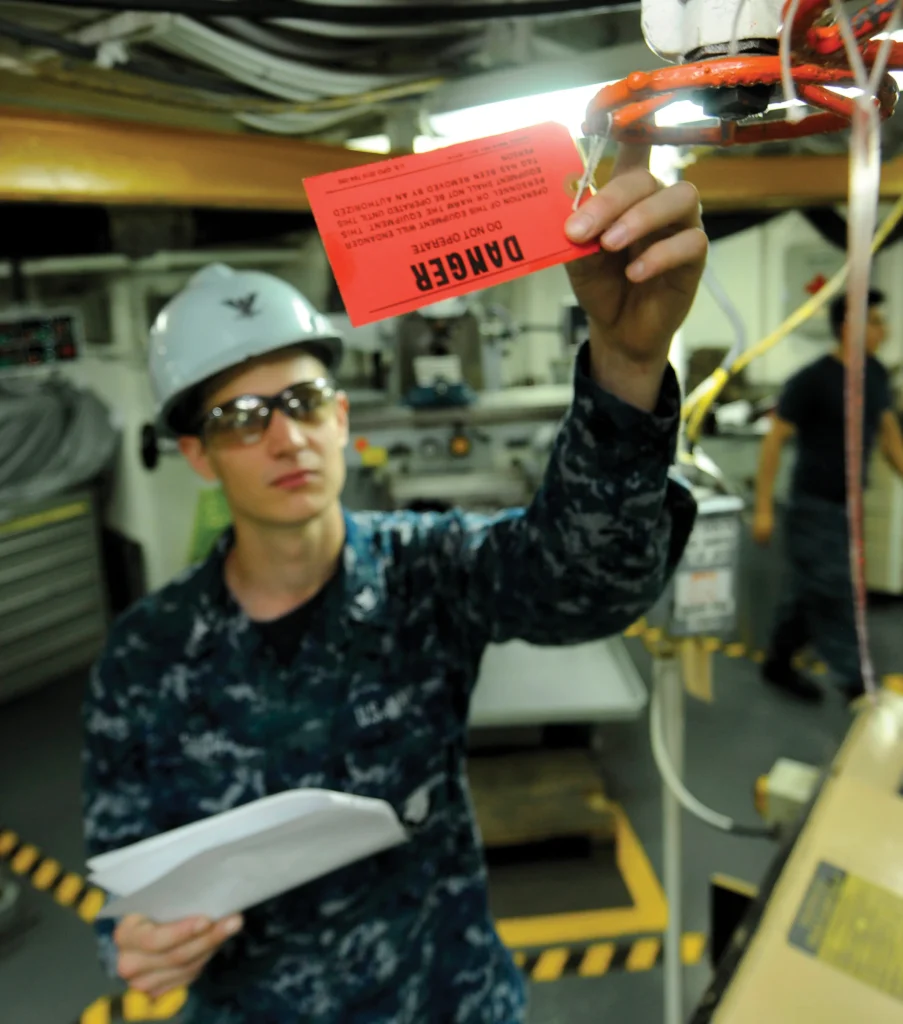

3.3 Maintenance and Work Control SOPs

This is where good ships separate themselves from “we get away with it”.

Typical SOPs

- Planned Maintenance System (PMS) execution and recording

- Defect reporting and temporary repairs

- Isolation standards: electrical isolation, mechanical isolation, valve line-up control

- Permit to Work workflows: hot work, enclosed space, working aloft, pressure systems, HV work

- LOTO discipline and tag control

- Tool control and job hazard briefing

- Reinstatement / testing / return-to-service procedures

Engineering truth

Most serious engine room incidents occur during maintenance, not during steady running—because barriers are removed, protections are bypassed, and the plant is in an abnormal configuration.

3.4 Emergency Response SOPs

These are not “drill scripts”. They are decision trees for seconds and minutes.

Typical SOPs

- Blackout response (including automatic recovery expectations and manual actions)

- Fire in machinery spaces (immediate actions, ventilation control, boundaries, fixed system release discipline)

- Flooding / bilge high-high response

- Loss of steering, loss of propulsion

- High crankcase mist / scavenge fire response (engine-specific)

- CO₂ release checklist and post-release recovery

- Major leak / fuel spray / hot surface fire prevention actions

Key principle

Emergency SOPs must define: who decides, who executes, and what must remain available (lights, comms, pumps, steering).

3.5 Environmental and Compliance SOPs

This is where “paperwork” becomes criminal exposure if wrong.

Typical SOPs

- OWS operation, testing, routine maintenance, and fault response

- Sludge handling, bilge transfers, incinerator operation (where fitted)

- Garbage segregation and engine room waste controls (oily rags, filters, chemicals)

- EGCS operation and monitoring (if fitted)

- BWMS operation and sampling discipline (if fitted)

- Recordkeeping: Oil Record Book, EGCS records, log extracts, port state readiness files

- Discharge rules by region and port restrictions

Reality check

Compliance systems assume disciplined operation and honest records. Many “detentions” begin with small inconsistencies: times don’t align, tank levels don’t reconcile, or logs show operations the plant physically could not have performed.

3.6 Information Management and Cyber SOPs

This is now an engine department issue, not an IT issue.

Typical SOPs

- Use of ECR computers (duty vs non-duty)

- USB prohibition and controlled media policy

- Password discipline and account control

- Vendor access procedures (remote support rules)

- Change management for automation logic and network devices

- Incident reporting for suspected cyber compromise

Operational truth

The easiest way to break a ship’s automation system is not hacking—it’s plugging something in.

4. Roles and Responsibilities in SOP Form

4.1 Chief Engineer (C/E) – procedural command

The C/E determines readiness standards and ensures the PMS, SMS, and compliance framework are active, practical, and followed. Core duties include:

- voyage needs planning (fuel, water, lubes, chemicals, spares)

- ensuring compliance with class/flag/port/SMS requirements

- ensuring PMS is updated and workable

- ensuring defects and abnormal machinery conditions are logged and actioned

- ensuring UMS procedures are followed when applicable

- ensuring OWS is treated as safety-critical equipment

- enforcing closed-loop communication

- enforcing work/rest and watch arrangements

- issuing standing orders and special instructions

- ensuring PTW/RA discipline and challenge culture

4.2 EOOW – operational authority on watch

The EOOW is the C/E’s representative and is responsible for safe and efficient operation of machinery and environmental protection during the watch:

- executes bridge orders promptly and safely

- maintains constant supervision of propulsion and auxiliaries

- conducts rounds, identifies abnormal conditions early

- manages the team, briefs ratings, controls hazards

- follows PTW/RA and coordinates maintenance with safe plant operation

- notifies bridge immediately of anything affecting propulsion/steering

- notifies C/E without delay when safety, pollution, or critical machinery is threatened

- takes immediate action when required even before notifying, if safety demands it

4.3 Ratings and wider engine room crew

Ratings operate inside the SOP framework: follow work orders, assist EOOW, comply with RA/PTW, maintain closed-loop comms, and know emergency equipment, alarms, escape routes.

5. Building an SOP Library That Doesn’t Collapse Under Its Own Weight

Because there are so many SOPs, the only way it works is with structure:

A) Critical Operations Register

A short list (often 15–30 items) that must have: procedure + checklist + training evidence.

B) SOP Index by System

Main engine · DGs · boilers · separators · pumps · instrumentation · HVAC · steering · deck machinery interfaces.

C) SOP Index by Operation

Arrival/departure · bunkering · fuel changeover · blackout · OWS ops · CO₂ release, etc.

D) Revision control

Every SOP needs: owner, revision date, reason for change, and “lessons learned” source.