Electrical Stability, Load Truth, and Why Blackouts Are Usually Self-Inflicted

ENGINE ROOM → Auxiliary & Support Systems

System Group: Electrical Power Generation & Distribution

Primary Role: Continuous, stable electrical supply to propulsion, safety, and hotel loads

Interfaces: Main Engines · PMS · Switchboards · Automation · Thrusters · Auxiliaries

Operational Criticality: Continuous

Failure Consequence: Load loss → blackout → propulsion degradation → safety escalation

Power generation is not about producing electricity.

It is about controlling load under uncertainty.

Position in the Plant

Electrical power generation sits beneath every other auxiliary system. Without it, pumps stop, valves freeze, controls die, and propulsion becomes blind and unstable.

From an engineering perspective, the power plant is the nervous system of the ship. It reacts instantly to disturbance, amplifies poor decisions, and punishes incorrect assumptions.

Generators rarely fail because of mechanical weakness.

They fail because load behaviour was misunderstood or mismanaged.

Contents

System Purpose and Design Intent

Generator Architecture and Load Characteristics

Power Management Systems and Reality

Load Sharing, Frequency, and Voltage Control

Transient Loads and Blackout Physics

Cooling, Lubrication, and Thermal Margins

Failure Development and Damage Progression

Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

1. System Purpose and Design Intent

The design intent of shipboard power generation is continuous availability, not peak output.

Generators are sized to accommodate:

- base hotel load

- auxiliary machinery

- propulsion support loads

- short-duration transients

They are not designed to absorb unlimited step load without consequence.

Electrical systems are inherently unforgiving. Frequency and voltage deviations propagate instantly, affecting every connected consumer simultaneously.

Stability, not capacity, defines survivability.

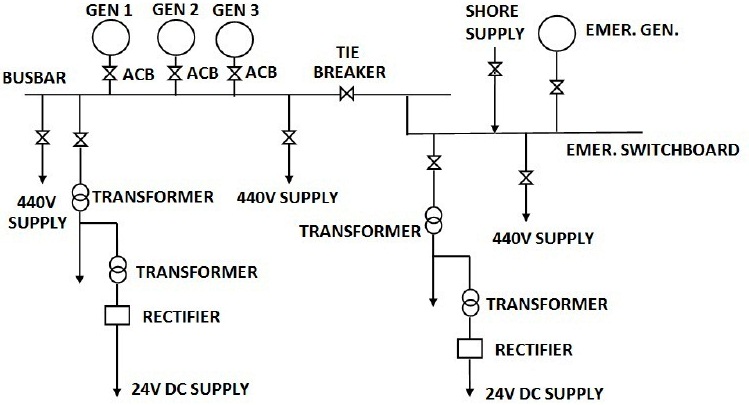

2. Generator Architecture and Load Characteristics

Marine generators operate under variable load profiles:

- steady cruising

- manoeuvring

- port operations

- emergency response

Each regime imposes different stresses on engines, alternators, and control systems.

Diesel generators experience:

- rapid torque demand changes

- governor response limits

- thermal lag

The alternator does not care why load changed.

It responds only to electrical demand.

Mechanical response always lags electrical disturbance.

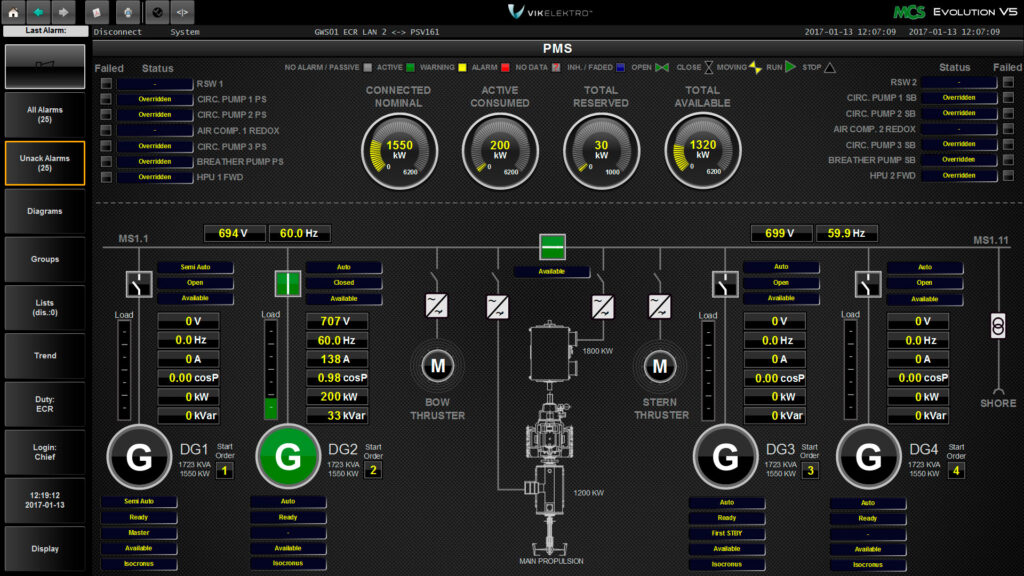

3. Power Management Systems and Reality

Power Management Systems (PMS) exist to automate decisions that are too fast for humans.

They control:

- generator start/stop

- load sharing

- blackout prevention

- preferential tripping

However, PMS logic is only as good as its assumptions.

Poorly configured PMS systems create false confidence. They appear to manage load while masking marginal conditions such as:

- overloaded generators operating near limits

- insufficient spinning reserve

- delayed load shedding

Automation hides instability until it cannot.

4. Load Sharing, Frequency, and Voltage Control

Load sharing is not about equality.

It is about dynamic balance.

Perfect load balance is rare. Small deviations are normal. Dangerous deviations grow silently.

Frequency reflects torque balance.

Voltage reflects excitation and reactive power.

Engineers who watch only one are blind to half the problem.

A generator holding voltage but losing frequency is losing mechanical control. A generator holding frequency but losing voltage is losing electrical margin.

5. Transient Loads and Blackout Physics

Blackouts are rarely caused by overload alone.

They are caused by rate of change.

Thrusters, large pumps, compressors, and steering gear introduce step loads faster than engines can respond.

If spinning reserve is insufficient, frequency collapses. Protective relays trip to save equipment — not operations.

Most blackouts are preventable through:

- load anticipation

- correct generator combinations

- disciplined operational sequencing

But only if engineers understand load behaviour, not just nameplate ratings.

6. Cooling, Lubrication, and Thermal Margins

Generators operate thermally close to limits.

Cooling systems must accommodate:

- high ambient engine room temperatures

- variable seawater temperature

- fouling and degradation

Lubrication failures often follow electrical stress. High load increases bearing temperature, oil breakdown, and wear.

A generator operating “normally” at elevated load is accumulating fatigue.

7. Failure Development and Damage Progression

Power generation failures develop through:

- marginal load sharing

- repeated transient stress

- thermal overload

- protective trips

- blackout

Mechanical failure is usually the final event, not the initiating one.

8. Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

Engineers protect the power plant by:

- maintaining adequate spinning reserve

- understanding transient load behaviour

- resisting convenience-driven shortcuts

Automation executes logic.

Judgement prevents catastrophe.

Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Power instability propagates into:

- propulsion response

- steering authority

- cooling and lubrication

- automation and alarms

Electrical failure expands faster than any other machinery failure on board.