Design Reality, Operational Risk & Engine-Room Consequences

Introduction

Cybersecurity at sea is no longer an IT problem. It is an engineering safety problem.

Modern ships and offshore units operate as floating industrial plants. Navigation, propulsion, power generation, cargo handling, ballast, DP, drilling, safety systems, and environmental compliance are all controlled, monitored, and optimised through networked digital systems. These systems were never designed with hostile access in mind, yet they are now routinely connected to shore networks, vendor systems, satellite links, and cloud services.

The result is simple:

a cyber failure can now create a physical casualty.

Cybersecurity in the maritime domain therefore sits at the intersection of IT (Information Technology) and OT (Operational Technology). The consequences of failure are not limited to data loss or inconvenience. They include loss of propulsion, loss of position, pollution events, fire escalation, well control loss, and threat to life.

This article addresses cybersecurity from an engineer’s perspective: what is connected, why it is vulnerable, how failures propagate, and what realistic, shipboard-applicable controls actually matter.

1. IT and OT Convergence – Why Ships Became Vulnerable

Historically, shipboard systems were isolated. Navigation stood alone. Machinery control was hard-wired. Logs were paper. Diagnostics required a technician onboard.

That world no longer exists.

Today, IT systems (email, crew welfare, admin networks) are routinely interconnected with OT systems (AMS, PMS, DP, cargo control, BWMS, EGCS, drilling control). This convergence improves efficiency and reduces operating cost — but it collapses isolation barriers that previously protected safety-critical systems.

A phishing email received on a crew terminal can now, if networks are poorly segmented, become a pathway toward:

- Alarm and Monitoring Systems (AMS)

- Power Management Systems (PMS)

- Navigation sensors and ECDIS

- DP controllers and thruster systems

- Cargo valve control

- Ballast Water Management Systems

- Engine automation PLCs

The danger is not theoretical. The weakest system is rarely the PLC — it is the human interface and legacy IT layer.

2. Network Architecture at Sea – What Is Actually Connected

A modern vessel or offshore unit typically contains multiple interlinked networks:

- Administrative IT network (email, reporting, crew internet)

- Navigation network (ECDIS, radar, GPS, AIS, gyro)

- Machinery control network (AMS, PLCs, HMIs)

- Power & propulsion network (PMS, generators, converters)

- Cargo or drilling control network

- Safety systems network (fire & gas, ESD interfaces)

- External connectivity (VSAT, Starlink, LTE, shore links)

In theory these networks are segmented. In practice, they are often bridged for:

- Remote diagnostics

- Vendor maintenance

- Performance monitoring

- Data logging and optimisation

- Regulatory reporting

Each bridge is an attack surface.

3. External Connectivity – Starlink, VSAT, and the New Reality

High-bandwidth satellite connectivity (Starlink, Ka-band VSAT) has transformed operations. It enables:

- Real-time diagnostics

- Remote troubleshooting

- Fleet optimisation

- AI-based analytics

- Crew welfare connectivity

But bandwidth is neutral. It amplifies both capability and risk.

Starlink’s low latency and high throughput remove the natural friction that previously limited cyber events at sea. A compromised endpoint is no longer “slow and isolated” — it is live, persistent, and externally reachable.

The risk is not Starlink itself.

The risk is connecting OT systems to the internet without engineering-grade security design.

Unlimited data does not mean unlimited trust.

4. Industrial Control Systems (ICS) – Why OT Is Different

OT systems are not hardened IT systems.

PLCs, HMIs, SCADA, DP controllers, drilling control systems, and safety PLCs are designed for:

- Deterministic operation

- High availability

- Predictable timing

- Physical process control

They are not designed for malware, encryption overhead, frequent patching, or antivirus scanning. Many run obsolete operating systems because certification, class approval, and vendor dependency prevent rapid updates.

This creates a dangerous mismatch:

high consequence systems with low cyber resilience.

Unlike IT, an OT failure may not “crash”. It may:

- Output false sensor values

- Accept manipulated setpoints

- Suppress alarms

- Delay safety actions

- Create unstable control loops

These failures are subtle, progressive, and hard to diagnose at sea.

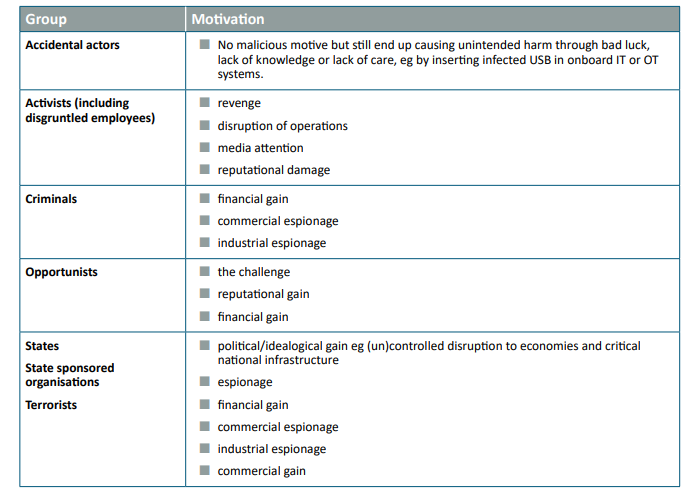

5. Threats That Matter at Sea

Maritime cyber threats are not abstract. The most relevant include:

- Phishing and spear-phishing targeting crew and contractors

- Malware and ransomware entering via email or USB

- GPS spoofing causing navigation and DP errors

- Unauthorized remote access by vendors or attackers

- Supply-chain compromise through software updates

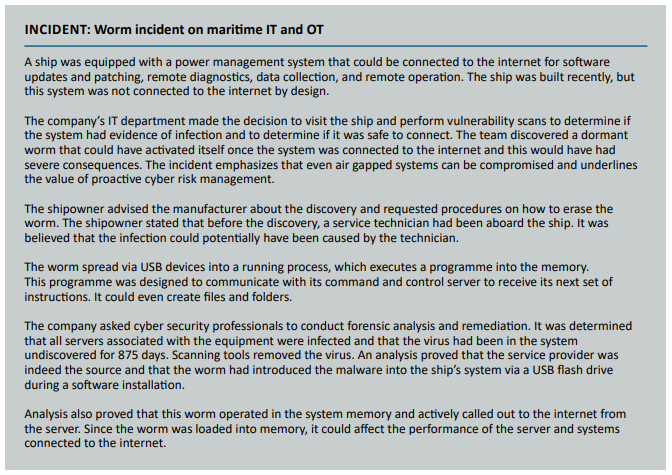

- Insider threats, intentional or accidental

- Denial-of-Service attacks on communications or control interfaces

The most common initial entry vector remains human behaviour, not technical weakness.

A single USB stick can defeat millions in hardware investment.

6. Functional Safety at Risk – When Cyber Meets Physics

Cybersecurity failures at sea escalate into functional safety failures.

Examples include:

- Manipulated GPS data leading to grounding or collision

- DP drift due to corrupted sensor inputs

- PMS instability causing blackout

- Cargo valve misoperation leading to spill

- Fire detection suppression delaying response

- Loss of well control functions on drilling units

At this point, cybersecurity is no longer about confidentiality.

It is about containment integrity and life safety.

This is why IMO, class societies, and flag states increasingly treat cyber risk as part of the vessel’s Safety Management System (SMS).

7. “IT Security by Design” – Why Isolation Alone No Longer Works

Traditional “defence in depth” relied on isolation. That strategy is collapsing under operational reality.

Ships require external access. Remote diagnostics are now standard. Data is monetised. Vendors expect connectivity.

The emerging requirement is security by design, meaning:

- Cybersecurity embedded at controller level

- Encrypted communications end-to-end

- Authentication enforced at system boundaries

- Minimal trust between zones

e - Deterministic behaviour preserved even under attack

This includes VPNs (OpenVPN, IPsec), encrypted controller-level communications, authenticated command channels, and strict control over who can touch what — and when.

8. Regulation and Accountability

Cyber risk management is no longer optional.

Key frameworks influencing ship design and operation include:

- IMO MSC-FAL.1/Circ.3 (Cyber Risk Management)

- ISM Code integration requirements

- IEC 62443 (Industrial Cybersecurity)

- NIST Cybersecurity Framework

- Class guidance (ABS, DNV, LR, BV)

- OCIMF and BIMCO recommendations

These frameworks do not prescribe equipment. They prescribe process, accountability, and discipline.

A ship that cannot demonstrate cyber risk management is non-compliant — regardless of whether it has been attacked.

9. Crew, Culture, and the Weakest Link

The most sophisticated system fails if the crew does not understand it.

Observed vulnerabilities onboard include:

- Shared passwords

- Default credentials

- Unauthorised USB use

- Open network ports

- Unpatched legacy systems

- Lack of awareness of phishing

- Poor control of vendor access

Cybersecurity training must be practical and role-specific. Engineers do not need theory. They need to know:

- What not to connect

- What to report

- What never to bypass

- What systems are critical

- Who authorises access

Cyber hygiene is now as fundamental as LOTO.

10. Incident Response – When Prevention Fails

No system is invulnerable.

A credible vessel cyber strategy includes:

- Clear incident reporting pathways

- Defined isolation procedures

- Ability to revert to manual or local control

- Offline backups of critical configurations

- Tested recovery procedures

- Class and flag notification protocols

The objective is containment and recovery, not blame.

A cyber incident handled early is survivable.

One handled late becomes a casualty.

Closing Reality

Ships are now cyber-physical systems.

Every network cable, remote connection, and USB port is a potential failure path between the digital world and steel, fuel, pressure, and motion.

Cybersecurity is no longer about protecting data.

It is about protecting people, propulsion, position, and pollution boundaries.

The most dangerous ship is not the one with poor cyber tools.

It is the one whose crew believes cyber is “someone else’s problem”.