Seeing Failure Before It Happens, and Why Data Without Judgement Is Dangerous

ENGINE ROOM → Propulsion & Transmission

System Group: Monitoring, Diagnostics & Prognostics

Primary Role: Early detection of degradation across propulsion systems

Interfaces: Engines · Gearboxes · Shafting · Bearings · Seals · Electrical Systems · Hull Structure

Operational Criticality: Continuous

Failure Consequence: Undetected degradation → secondary damage → loss of propulsion availability

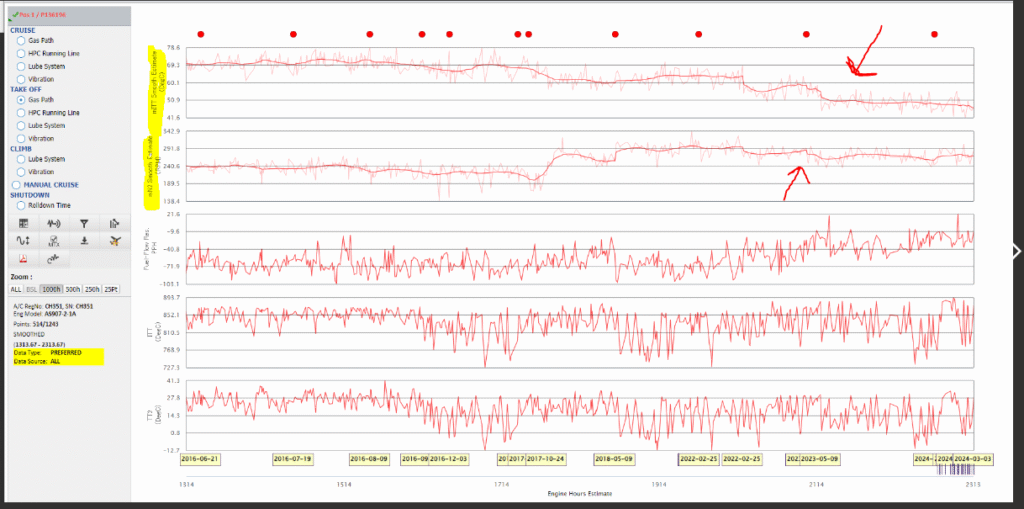

Condition monitoring does not prevent failure.

It reveals the trajectory toward failure early enough for intervention.

Position in the Plant

Condition monitoring exists above individual systems. It does not cool, lubricate, steer, or propel. Instead, it observes how those systems behave under load, over time, and under deviation.

In modern plants, monitoring has expanded rapidly — vibration sensors, oil analysis, temperature arrays, electrical diagnostics, and data logging. Yet the failure rate of machinery has not declined proportionally.

The reason is simple: data is passive.

Judgement is active.

Condition monitoring is only effective when engineers understand what normal degradation looks like, and when a trend represents a change in physics rather than noise.

Contents

Purpose and Design Intent of Condition Monitoring

Degradation vs Failure: Understanding the Gap

Vibration Monitoring and Its Limits

Oil and Wear Debris Analysis

Thermal Monitoring and False Stability

Electrical Condition Monitoring

Trend Interpretation and Cross-Correlation

Failure Development and Diagnostic Blind Spots

Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

1. Purpose and Design Intent of Condition Monitoring

The intent of condition monitoring is time.

Time to plan maintenance.

Time to reduce load.

Time to avoid secondary damage.

It does not eliminate wear. It reveals when wear transitions from acceptable to destructive.

Monitoring systems are therefore designed to detect rate of change, not absolute condition. A bearing does not fail because it is warm. It fails because it is warming faster than it should.

2. Degradation vs Failure: Understanding the Gap

Most machinery operates in a degraded state for the majority of its life.

This degradation is often benign:

- surface polishing

- gradual clearance increase

- predictable wear patterns

Failure occurs when degradation crosses a threshold where damage becomes self-accelerating.

Condition monitoring is about identifying that threshold early — not about chasing perfection.

The most dangerous systems are those that degrade quietly while remaining within alarm limits.

3. Vibration Monitoring and Its Limits

Vibration analysis is powerful, but not omniscient.

It detects:

- imbalance

- misalignment

- bearing distress

- gear mesh anomalies

However, vibration signals are filtered through structure, damping, and operational variability. A cracked bearing cage may remain invisible until damage is advanced.

Trend direction matters more than amplitude.

Frequency content matters more than overall RMS.

A “stable” vibration level that shifts in character is more significant than a sudden spike.

4. Oil and Wear Debris Analysis

Oil analysis reveals what vibration cannot: material loss.

Key indicators include:

- ferrous and non-ferrous particle counts

- water ingress

- additive depletion

- oxidation products

However, oil analysis is retrospective. It shows what has already happened.

The danger lies in misinterpreting single samples. Wear trends must be correlated with operating history, load changes, and maintenance actions.

Clean oil does not guarantee healthy machinery.

Dirty oil guarantees unhealthy machinery.

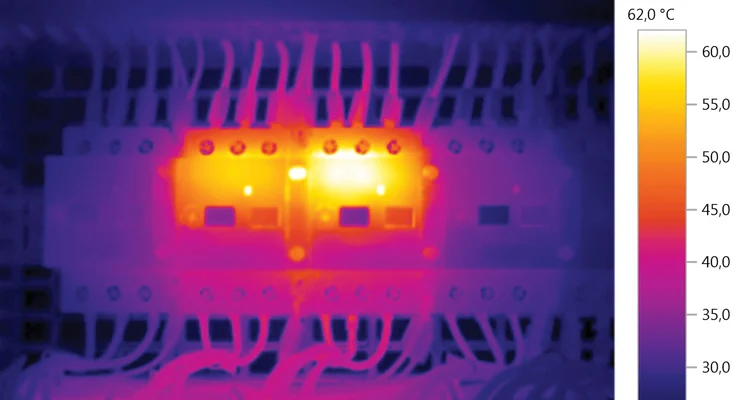

5. Thermal Monitoring and False Stability

Temperature is a late indicator.

By the time a bearing runs hot, lubrication failure has already occurred. Thermal monitoring is therefore best used to confirm hypotheses raised by other indicators.

Uniform temperature rise across a system may indicate load increase. Localised rise indicates distress.

The most dangerous condition is thermal stability at elevated load, where damage accumulates without alarm.

6. Electrical Condition Monitoring

In electric and hybrid propulsion systems, electrical diagnostics are structural indicators.

Insulation resistance, partial discharge, harmonic distortion, and load imbalance all reveal degradation pathways invisible mechanically.

Electrical failures rarely fail gracefully. Insulation breakdown is often sudden and terminal.

Electrical monitoring must therefore be conservative and trend-focused.

7. Trend Interpretation and Cross-Correlation

No single monitoring method is sufficient.

Effective condition monitoring cross-correlates:

- vibration changes

- oil debris trends

- thermal behaviour

- operational events

A vibration increase following heavy manoeuvring has different significance than the same increase during steady cruising.

Context converts data into diagnosis.

8. Failure Development and Diagnostic Blind Spots

Condition monitoring does not detect:

- poor design margins

- incorrect operation

- one-off overload events

Many failures occur immediately after maintenance, alignment work, or configuration changes — moments when monitoring systems are least trusted.

Blind reliance on sensors creates false confidence.

9. Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

Condition monitoring is a tool, not a substitute for engineering.

Engineers add value by:

- questioning stable but abnormal trends

- recognising pattern repetition

- correlating behaviour across systems

A system trending “normally” toward failure is still trending toward failure.

Judgement decides when to intervene.

Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Condition monitoring influences:

- maintenance planning

- operational limits

- spare strategy

- propulsion availability

Without interpretation, it becomes noise. With judgement, it becomes foresight.