Elastic Reality, Resonance Risk, and Why Perfect Alignment Does Not Exist

ENGINE ROOM → Propulsion & Transmission

System Group: Structural Dynamics & Power Transmission Integrity

Primary Role: Control of mechanical stress and vibration within acceptable limits

Interfaces: Engine · Gearbox · Shafting · Bearings · Hull Structure · Propeller

Operational Criticality: Continuous

Failure Consequence: Fatigue cracking → bearing failure → shaft damage → propulsion loss

Alignment and vibration are not conditions to be eliminated.

They are realities to be managed.

Position in the Plant

Every rotating propulsion system is elastic. Shafts twist, hulls bend, bearings move, and loads fluctuate.

Alignment is therefore not a fixed state, but a band of acceptable distortion within which machinery can survive.

Torsional vibration is the dynamic expression of this elasticity. It cannot be removed, only controlled.

Contents

Alignment Purpose and Design Intent

Elastic Shaftlines and Hull Interaction

Cold Alignment vs Hot Alignment Reality

Torsional Vibration Fundamentals

Critical Speeds and Resonance

Measurement, Monitoring, and Interpretation

Failure Development and Damage Progression

Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

1. Alignment Purpose and Design Intent

The purpose of alignment is load distribution, not straightness.

Bearings must share load evenly. Shafts must operate within allowable bending and shear limits.

Perfect alignment on shore guarantees misalignment at sea.

Design intent therefore allows controlled misalignment under known conditions.

2. Elastic Shaftlines and Hull Interaction

Hull deflection varies with:

- loading condition

- ballast state

- wave action

- thermal gradients

These movements shift bearing positions continuously.

Shaftlines must tolerate this motion without concentrating load.

Over-stiff systems fail faster than compliant ones.

3. Cold Alignment vs Hot Alignment Reality

Cold alignment is a starting point.

Hot alignment — under operating temperature and load — defines real behaviour.

Thermal growth of engines and gearboxes alters geometry significantly. Ignoring this leads to edge loading and premature bearing failure.

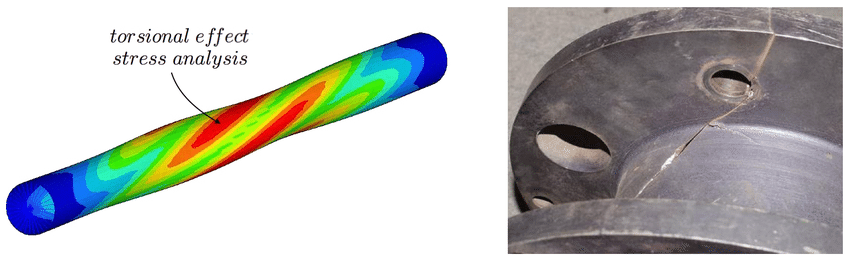

4. Torsional Vibration Fundamentals

Combustion is not continuous. It is impulsive.

Each firing event introduces torque fluctuation into the shaftline. This produces torsional oscillation.

If oscillation frequency coincides with natural system frequency, resonance occurs.

Resonance amplifies stress dramatically.

5. Critical Speeds and Resonance

Critical speeds are not theoretical curiosities.

Operating continuously within barred speed ranges accelerates:

- fatigue cracking

- coupling failure

- gear tooth damage

Avoidance relies on operational discipline, not just design.

6. Measurement, Monitoring, and Interpretation

Vibration monitoring provides data, not answers.

Engineers interpret:

- amplitude

- frequency

- phase relationships

Trend deviation matters more than absolute values.

A quiet system can still be destructive.

7. Failure Development and Damage Progression

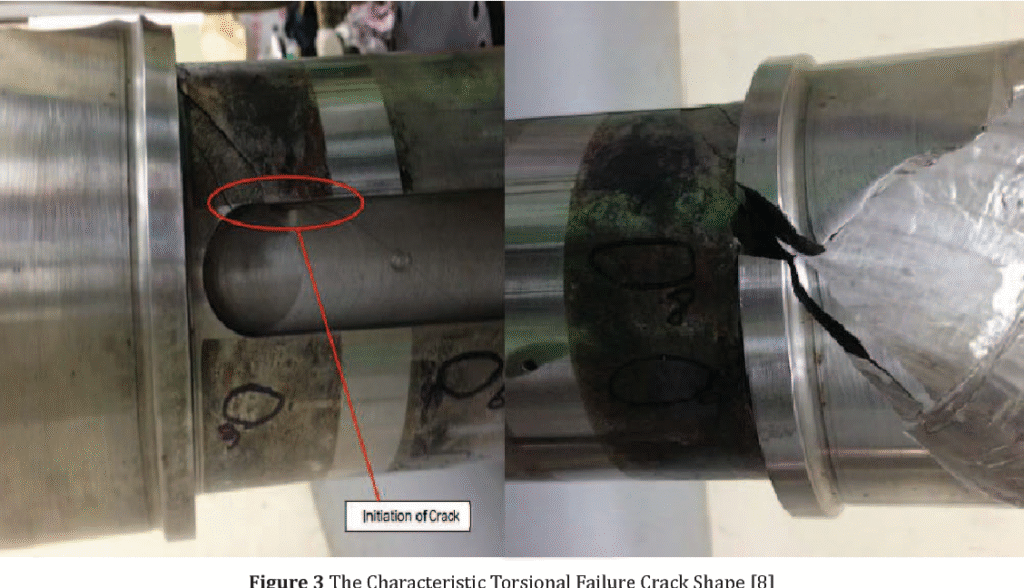

Misalignment and vibration failures progress through:

- uneven bearing loading

- oil film breakdown

- micro-crack initiation

- fatigue propagation

- sudden failure

By the time noise or heat appears, structural damage is often advanced.

8. Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

No alarm announces “alignment is deteriorating”.

Engineers detect it through:

- vibration character

- bearing behaviour

- oil debris trends

Judgement, not instrumentation, prevents catastrophic failure.

Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Alignment and vibration influence:

- gearbox life

- seal integrity

- propeller loading

- hull fatigue

Every propulsion system failure has an alignment component.