ENGINE ROOM → Control & Operations

Position in the Plant

System Group: Control & Operations

Primary Role: Convert physical reality into measurable signals for control, protection, and decision-making

Interfaces: Automation (IAS/AMS), navigation systems, propulsion, auxiliaries, safety systems

Operational Criticality: Absolute

Failure Consequence: False situational awareness → delayed or incorrect decisions → machinery damage, grounding, collision, or regulatory breach

Ships do not operate on reality.

They operate on measured representations of reality.

Every operational decision on board — from power management to navigation, from cargo handling to emergency response — depends on sensors. If the data is wrong, incomplete, or misleading, the ship is blind regardless of how experienced the crew may be.

Introduction

Shipboard instrumentation exists to translate a hostile, dynamic physical environment into usable information. Temperature, pressure, speed, depth, position, stress, and flow are not abstract concepts at sea; they are survival parameters.

Modern vessels carry thousands of sensors. Most work continuously and invisibly. Their success is measured by silence. Their failure is often not obvious until consequences emerge elsewhere in the plant.

Instrumentation does not fail loudly.

It fails by lying convincingly.

Contents

- Purpose and Design Intent of Marine Instrumentation

- Navigation and Positioning Sensors

- Machinery and Performance Instrumentation

- Safety and Environmental Monitoring

- Structural, Stability, and Cargo Monitoring

- Data Recording, Integration, and Automation Dependency

- Sensor Failure Modes and Trust Degradation

- Engineering Judgement Beyond the Numbers

1. Purpose and Design Intent of Marine Instrumentation

Instrumentation exists to reduce uncertainty.

Ships operate in environments where direct observation is limited. Engines run enclosed. Tanks are opaque. Hull stresses are invisible. External conditions change faster than human perception. Sensors extend human awareness beyond these limits.

However, instrumentation is not installed to provide perfect knowledge. It is installed to provide sufficient information for safe operation within defined margins. Those margins are regulatory, commercial, and technical compromises.

Understanding what a sensor was designed to indicate — and what it was never intended to reveal — is fundamental to using it correctly.

2. Navigation and Positioning Sensors

Navigation instrumentation defines the vessel’s relationship with the external world. These sensors underpin collision avoidance, passage planning, and compliance with international regulations.

Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers provide continuous positional data, forming the backbone of modern navigation. While highly accurate, GPS is vulnerable to signal degradation, multipath errors, jamming, and spoofing. Over-reliance on GPS without cross-checking against other navigation cues introduces systemic risk.

Speed logs measure speed through water, not speed over ground. This distinction matters for propulsion efficiency, hull performance monitoring, and manoeuvring in current. Fouling, air ingestion, or sensor misalignment can quietly corrupt readings.

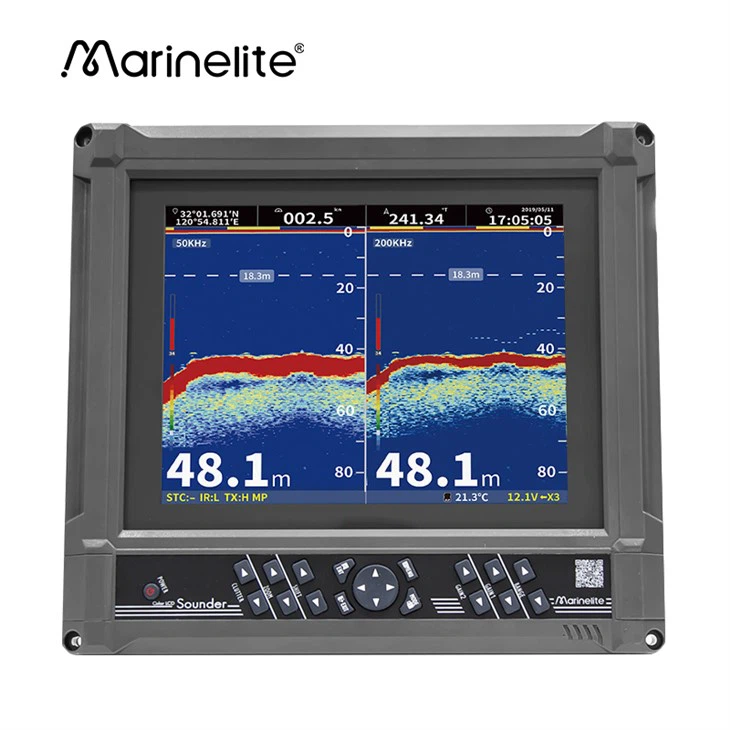

Echo sounders determine under-keel clearance. Their accuracy depends on sound velocity assumptions, seabed reflectivity, and transducer condition. Shallow-water errors are common and often misinterpreted as sudden depth changes.

Gyro compasses provide true heading independent of magnetic influence. They are mechanically and electrically complex, sensitive to power quality, and prone to drift under certain dynamic conditions. When they fail, they often degrade gradually rather than stopping outright.

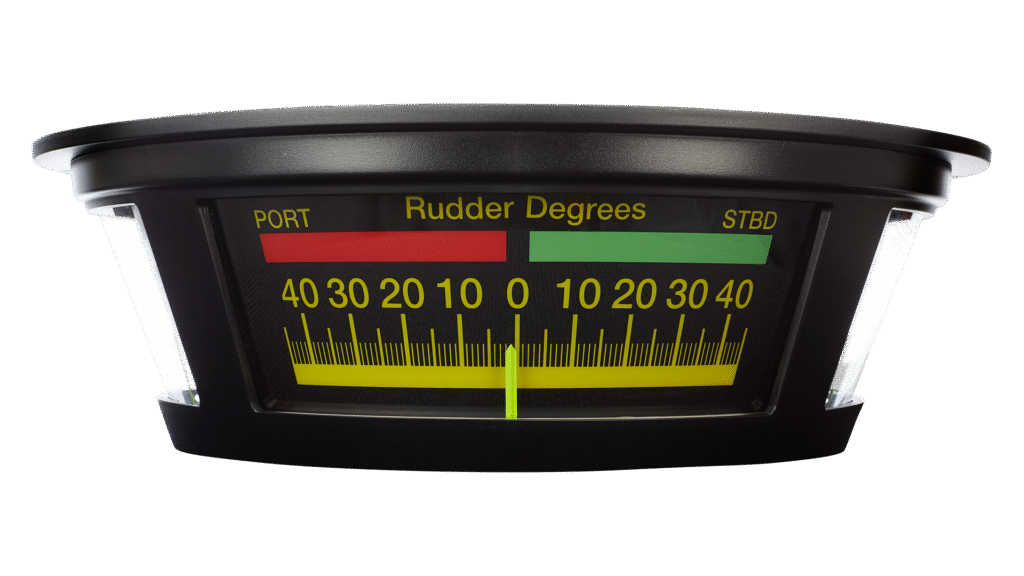

Rudder angle indicators close the loop between bridge command and steering gear response. Discrepancies between commanded and indicated rudder angle are often the first sign of steering system degradation.

Navigation sensors rarely fail catastrophically. They fail by diverging from one another.

3. Machinery and Performance Instrumentation

Machinery instrumentation forms the backbone of engine room decision-making. It monitors the internal state of systems that cannot be directly observed.

Temperature sensors track thermal limits in engines, boilers, coolers, bearings, and exhaust systems. Their placement is critical. A sensor measures temperature at its own location, not necessarily at the point of maximum stress. Drift or insulation degradation can mask dangerous hotspots.

Pressure sensors monitor fuel oil, lubricating oil, cooling water, hydraulic systems, and cargo lines. Pressure is often used as a proxy for flow and system health, but pressure alone does not confirm circulation. A blocked system can show normal pressure while starving components downstream.

Flowmeters provide direct insight into system performance, but are sensitive to density changes, air entrainment, fouling, and installation geometry. Incorrect flow data leads directly to incorrect fuel consumption analysis and cooling assessments.

Vibration sensors and accelerometers monitor rotating machinery and structural response. They are powerful tools for condition monitoring, but only when trends are understood. Raw vibration numbers without baseline context are meaningless.

RPM indicators and torque meters define propulsion load. Shaft power measurements are essential for performance optimisation and detecting mechanical degradation. Errors here propagate directly into fuel efficiency calculations and load management decisions.

Machinery sensors rarely trigger immediate alarms when they fail. Instead, they create false confidence.

4. Safety and Environmental Monitoring

Safety instrumentation exists to detect conditions humans cannot sense reliably or quickly enough.

Radar provides situational awareness beyond visual range and in restricted visibility. While not traditionally considered “instrumentation” in the engine room sense, radar data integrates into the ship’s overall sensor ecosystem.

Anemometers measure wind speed and direction, influencing manoeuvring decisions, mooring loads, and cargo operations. Local turbulence and sensor placement errors are common sources of misleading data.

Gas sensors detect flammable, toxic, or asphyxiant gases in machinery spaces, cargo areas, and enclosed spaces. Sensor poisoning, calibration drift, and delayed response are well-known failure modes.

Level sensors — whether radar, ultrasonic, float, or pressure-based — monitor tanks for overfill prevention and inventory control. Foam, vapour, temperature stratification, and density changes routinely compromise accuracy.

Bilge alarms provide the last line of defence against flooding. They are simple devices, but among the most frequently bypassed or ignored due to nuisance alarms. When a bilge alarm activates legitimately, response time is often already critical.

5. Structural, Stability, and Cargo Monitoring

Large vessels rely increasingly on instrumentation to monitor hull and cargo behaviour.

Strain gauges and accelerometers measure hull stress, vibration, and fatigue loading. These systems do not prevent structural damage; they reveal when operating patterns are eroding structural margins.

Draft, trim, and heel sensors quantify vessel stability and loading condition. Errors here affect compliance, fuel efficiency, and safety. Sensor offsets after drydock are common and frequently overlooked.

Humidity and temperature sensors in cargo spaces protect sensitive cargo and prevent condensation damage. Their reliability depends on airflow, placement, and maintenance, not just calibration.

Cargo monitoring instrumentation often spans both deck and engine departments, making ownership and accountability ambiguous — a common source of neglected faults.

6. Data Recording, Integration, and Automation Dependency

Voyage Data Recorders (VDRs) collect sensor data, bridge audio, radar images, and alarms to support incident investigation. They do not prevent accidents; they explain them afterwards.

Automation systems consume sensor data continuously. Control decisions, alarms, shutdowns, and interlocks depend entirely on sensor integrity. A failed sensor does not merely remove information; it reshapes system behaviour.

Automation trusts sensors implicitly. Humans must not.

7. Sensor Failure Modes and Trust Degradation

Sensors fail through:

- drift rather than breakage

- contamination rather than destruction

- calibration loss rather than disconnection

The most dangerous sensor is not one that fails and alarms.

It is one that remains believable while wrong.

Single-sensor reliance is therefore a design compromise, not a best practice. Cross-checking between independent measurements, local gauges, and physical observation remains essential.

Sensor Drift, Degradation, and the Illusion of Accuracy

Sensor drift is not a defect.

It is an expected consequence of time, environment, and service.

In shipboard systems, sensor drift refers to the gradual, unintended change in a sensor’s output despite no meaningful change in the actual physical condition being measured. The machinery may be stable, but the signal describing it slowly moves away from reality. This degradation occurs quietly, incrementally, and almost always without triggering alarms.

Drift is therefore one of the most dangerous failure modes in marine instrumentation. A failed sensor is obvious. A drifting sensor is trusted.

The Nature of Drift in Marine Environments

Marine sensors operate in conditions that accelerate degradation. Temperature cycles from cold starts to full load, constant vibration, oil mist, salt-laden air, humidity, and chemical exposure all act on sensing elements and electronics simultaneously.

Electronic components age. Resistance values shift. Capacitors change behaviour. Mechanical sensing elements experience relaxation, creep, and fatigue. Optical paths become coated. Pressure ports accumulate residue. None of this happens suddenly, and none of it looks like a fault in isolation.

The sensor continues to produce a plausible signal.

The automation system continues to believe it.

This is why drift is rarely detected by alarms. Alarm limits are crossed only when drift becomes extreme. Long before that, the plant may already be operating outside its intended envelope.

Causes of Sensor Drift in Shipboard Service

Environmental exposure is the dominant driver. Temperature fluctuations alter material properties and electronic reference points. Humidity promotes corrosion and condensation. Vibration loosens connections and accelerates wear. Chemical exposure — fuel vapours, cleaning agents, exhaust products — attacks seals and sensing surfaces.

Component aging compounds this effect. Sensors are not static devices. Their internal reference points degrade over time even under ideal conditions. In a shipboard environment, this degradation is accelerated.

Contamination is particularly insidious. Dust, oil mist, soot, scale, or biological growth accumulate slowly, changing sensor response characteristics rather than blocking them outright. The sensor still works — it simply works differently.

Physical stress also plays a role. Repeated pressure cycles, thermal expansion, and mechanical strain alter internal geometry. Materials relax. Zero points shift. Sensitivity changes.

Installation quality and usage complete the picture. Poor mounting, incorrect orientation, impulse lines with air or sludge, or sensors installed in marginal locations may drift far faster than identical devices installed correctly.

Types of Sensor Drift and How They Manifest

The most common form is zero drift, also known as offset drift. Here, the sensor reports a non-zero output when the true input is zero. A pressure sensor may indicate pressure when the system is depressurised. A temperature sensor may read warm when cold. Offset drift shifts the baseline of decision-making.

More dangerous is sensitivity drift, where the relationship between input and output changes. The sensor still reads zero correctly, but its response to changes is distorted. A pressure increase produces less apparent change than it should. A temperature rise appears slower or smaller. This type of drift masks rate-of-change — precisely the parameter most relevant to early fault detection.

Sensitivity drift is rarely obvious without comparison to an independent reference.

Operational Consequences of Drift

Drifting sensors do not simply produce incorrect numbers. They alter system behaviour.

Automation systems rely on sensor inputs to regulate, alarm, and protect. A drifting sensor may delay alarms, suppress protective actions, or initiate incorrect control responses. Fuel consumption calculations become unreliable. Cooling margins appear healthy when they are not. Load limits are approached unknowingly.

False alarms are one outcome. Silent damage is another.

In systems requiring tight control — combustion, lubrication, cooling, stability, cargo handling — drift directly undermines safety margins.

Managing Drift: Reality, Not Theory

Calibration is the primary control measure, but calibration only corrects what is known. A sensor that has drifted beyond calibration range or behaves non-linearly may pass a basic check while still being unreliable under dynamic conditions.

Stabilisation matters. Sensors require time to acclimate after installation, overhaul, or major environmental change. Immediate trust in readings after startup is misplaced.

Cleaning restores performance only when contamination is superficial. Internal fouling, chemical attack, or aged electronics cannot be cleaned away.

Replacement is not failure; it is lifecycle management. Sensors are consumable components, even when they appear intact.

Most importantly, cross-comparison remains essential. Local gauges, redundant sensors, trend behaviour, and physical observation provide context that no single sensor can offer.

Engineering Reality

Instrumentation provides precision, not truth.

A value displayed with three decimal places may be less accurate than a vibrating needle on a local gauge. The difference is not technology — it is proximity to reality.

Experienced engineers do not ask “what does the sensor say?”

They ask “why does it say that?”

Sensor drift ensures that this question is always relevant.

8. Engineering Judgement Beyond the Numbers

Instrumentation provides data.

Engineering provides interpretation.

A calm display does not guarantee a healthy plant. A noisy display does not always indicate danger. Experienced engineers recognise patterns, not just values.

Sensors extend perception. They do not replace understanding.