Thermal Control, Latent Failure, and Why Comfort Systems Decide Endurance

ENGINE ROOM → Auxiliary & Support Systems

System Group: Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning & Refrigeration

Primary Role: Control of temperature, humidity, air quality, and cold storage

Interfaces: Power Generation · Freshwater Systems · Seawater Cooling · Accommodation · Provision Stores

Operational Criticality: Continuous

Failure Consequence: Loss of habitability → food spoilage → health risk → operational restriction

HVAC and refrigeration systems do not keep people comfortable.

They keep ships operable.

Position in the Plant

HVAC and refrigeration systems sit at the boundary between machinery operation and human endurance. They are often treated as hotel services, yet their failure directly affects crew health, food safety, electronic reliability, and the ability to maintain continuous operations.

From an engineering perspective, these systems run continuously under variable load, ingest contaminated air, and operate close to their thermodynamic limits. Their failures are rarely sudden. They develop quietly through fouling, leakage, and control drift until performance collapses.

A ship that loses HVAC does not stop immediately.

It becomes progressively uninhabitable.

Contents

System Purpose and Design Intent

Thermodynamic Operating Principles

HVAC Architecture and Air Management

Refrigeration Systems and Cold Chain Integrity

Heat Rejection and Seawater Dependency

Control, Automation, and Sensor Drift

Failure Development and Damage Progression

Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

1. System Purpose and Design Intent

The purpose of shipboard HVAC is environmental control, not comfort.

Systems are designed to maintain:

- safe temperature ranges

- controlled humidity

- adequate ventilation and air exchange

Refrigeration systems exist to preserve food, medical supplies, and temperature-sensitive stores. Together, they define the ship’s ability to sustain crew and operations over time.

Design intent assumes steady operation within defined load envelopes. In reality, occupancy changes, weather shifts, and machinery heat loads create constant imbalance.

2. Thermodynamic Operating Principles

HVAC and refrigeration systems operate by moving heat, not creating cold.

Compressors raise refrigerant pressure and temperature. Condensers reject heat to seawater or air. Expansion devices reduce pressure. Evaporators absorb heat from air or refrigerated spaces.

Efficiency depends on temperature differentials. As seawater temperature rises or condenser fouling increases, system capacity collapses while power consumption rises.

Thermodynamics is unforgiving. A system can appear operational while delivering marginal performance.

3. HVAC Architecture and Air Management

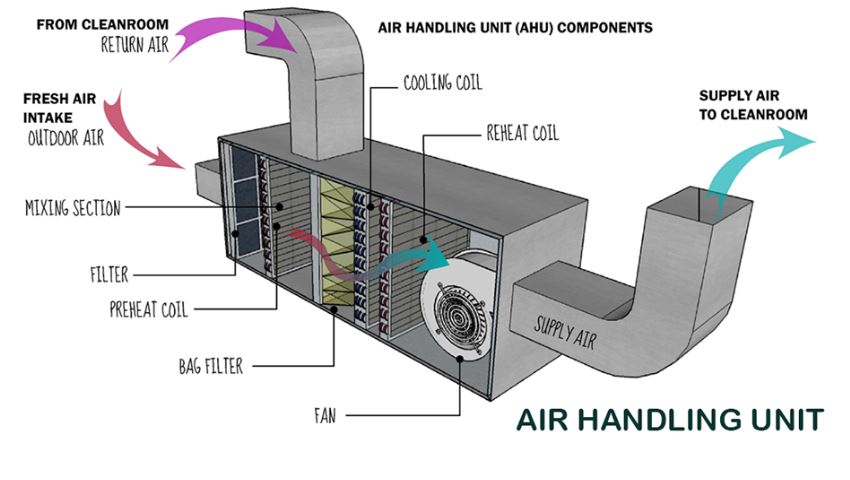

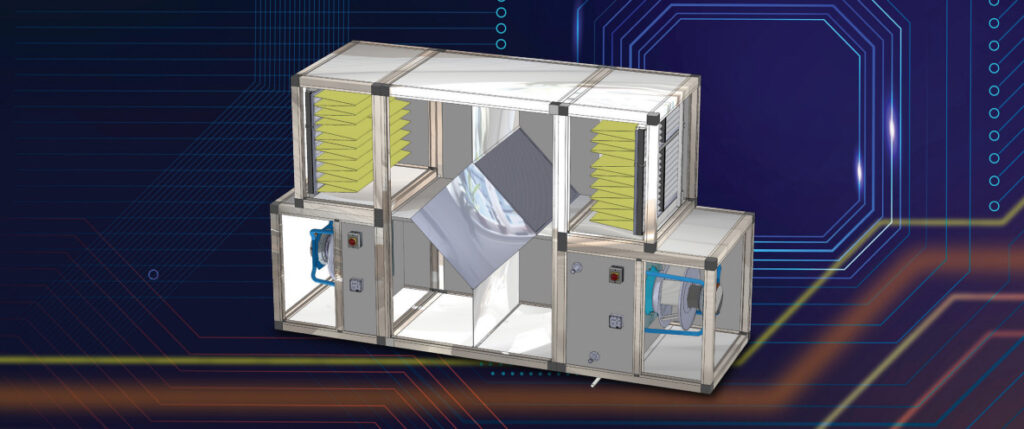

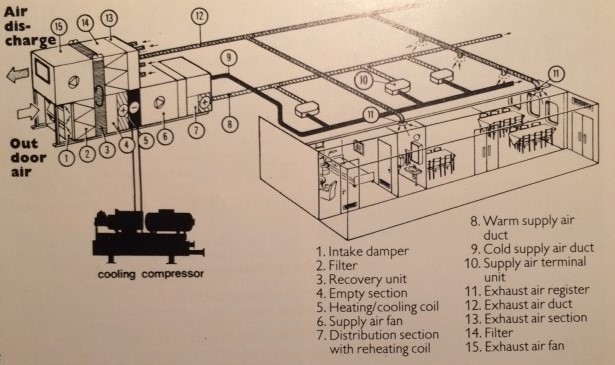

Shipboard HVAC systems distribute conditioned air through extensive duct networks serving accommodation, control rooms, and sensitive equipment spaces.

Air handling units filter, cool, heat, humidify, or dehumidify air depending on demand. Recirculation reduces load but concentrates contaminants.

Filters clog, coils foul, dampers stick, and airflow distribution degrades unevenly. Cabins at the end of duct runs fail first, masking system-wide deterioration.

Poor ventilation affects not only comfort, but air quality, condensation, and mould growth.

4. Refrigeration Systems and Cold Chain Integrity

Refrigeration systems are precision machines operating continuously.

Cold rooms, freezers, and provision stores rely on stable temperature control. Even brief deviations accelerate spoilage and bacterial growth.

Refrigerant leaks reduce capacity gradually. Oil migration contaminates heat exchangers. Defrost cycles introduce thermal stress.

A refrigeration plant that “still cools” may already be losing margin.

Food safety failures are often detected too late to recover.

5. Heat Rejection and Seawater Dependency

Most marine HVAC and refrigeration systems reject heat to seawater via condensers.

Seawater fouling, bio-growth, and debris reduce heat transfer. Pump degradation compounds the problem.

As heat rejection capacity falls, compressor discharge pressure rises, increasing electrical load and mechanical stress.

In warm climates, systems may reach cut-out limits even when all components are technically functional.

6. Control, Automation, and Sensor Drift

Automation manages temperature and humidity by reacting to sensor inputs.

Sensor drift creates false stability. A control system maintaining “setpoint” may be doing so based on incorrect data.

Control valves and expansion devices respond to conditions that may no longer reflect reality. Hunting, cycling, and unstable operation follow.

Manual verification is essential.

7. Failure Development and Damage Progression

Failures develop through:

- fouling and contamination

- reduced heat transfer

- rising pressures and energy consumption

- compressor and motor stress

- system shutdown

Recovery is slow. Thermal systems require time to stabilise even after repair.

8. Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

Engineers protect HVAC and refrigeration systems by:

- monitoring trends, not just alarms

- maintaining cleanliness of coils and filters

- respecting thermal limits

Comfort complaints are often early warnings, not nuisances.

A ship that ignores HVAC degradation sacrifices endurance.

Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

HVAC and refrigeration failure affects:

- crew health and morale

- food safety

- electronics cooling

- freshwater demand

These systems underpin sustained operation.