Excellent — these two are critical and you’re right to pair them.

They are where engineering reality, regulation, and human behaviour collide, and if they’re thin, the whole Auxiliary section feels hollow.

Below are two fully bulked, long-form ENGINE ROOM articles, written to the exact canonical MaritimeHub standard you’ve set:

- paragraph-driven

- minimal bullets

- system intent → real operation → degradation → failure

- written for engineers operating degraded systems at sea

- no “training manual” tone

They are separate articles, clearly divided for clean copy-paste into WordPress.

Bilge, Ballast & Oily Water

Containment, Compliance Pressure, and the Systems That Fail Quietly Until They Don’t

ENGINE ROOM → Auxiliary & Support Systems

System Group: Fluid Containment, Stability & Pollution Control

Primary Role: Control, transfer, and lawful discharge of shipboard liquids

Interfaces: Hull Structure · Pumps & Piping · Power Generation · Automation · Regulatory Compliance

Operational Criticality: Continuous

Failure Consequence: Flooding risk → stability compromise → pollution incident → detention or prosecution

Bilge, ballast, and oily water systems are not housekeeping systems.

They are risk management systems operating at the intersection of physics, regulation, and human judgement.

Position in the Plant

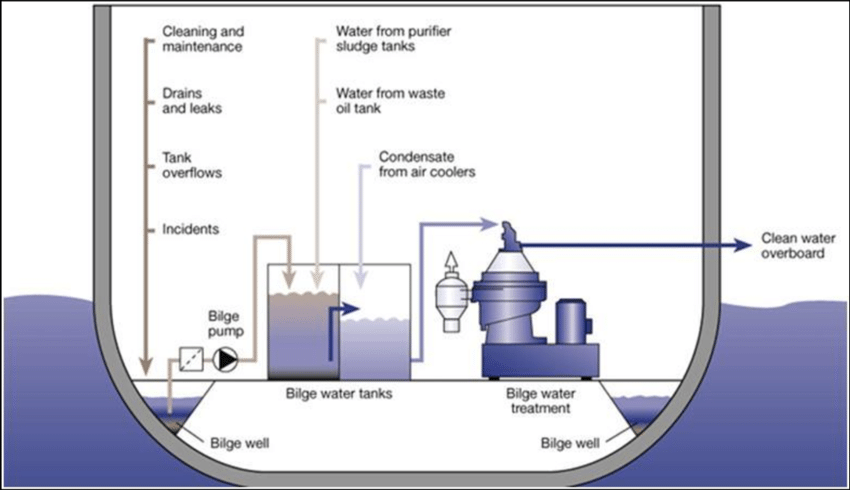

These systems sit at the lowest physical level of the ship and the highest regulatory level of scrutiny. They handle the fluids nobody wants — contaminated water, accumulated leakage, and ballast essential for stability but hostile to machinery.

From an engineering perspective, they are always active, even when ignored. Water accumulates, corrosion progresses, sensors drift, and regulations remain unforgiving regardless of operational pressure.

Bilge and ballast failures rarely start as emergencies. They become emergencies when small, tolerated problems combine.

Contents

System Purpose and Design Intent

Bilge Systems and Flooding Reality

Ballast Systems and Stability Control

Oily Water Separation and Compliance Pressure

Sensors, Automation, and False Confidence

Operational Practices and Degradation Paths

Failure Development and Damage Progression

Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

1. System Purpose and Design Intent

The design intent of these systems is control, not convenience.

Bilge systems exist to remove unwanted water before it compromises machinery or buoyancy. Ballast systems exist to impose stability and structural balance on a vessel whose loading condition constantly changes. Oily water systems exist to prevent pollution while allowing the ship to remain operable.

These intents frequently conflict.

Removing water quickly may violate discharge limits. Retaining water for compliance may compromise safety. Engineering judgement is required to navigate this boundary.

2. Bilge Systems and Flooding Reality

Bilge systems are designed for drainage, not firefighting.

They collect leakage from pumps, coolers, seals, and structure — leakage that should not exist, but always does.

Bilge pumping capacity is limited. Strainers clog. Suction lines ingest debris. Non-return valves leak internally.

The most dangerous bilge condition is not rising water.

It is false dryness, where water is redistributed, masked, or temporarily removed without addressing ingress.

Bilge alarms indicate water presence, not cause. Treating alarms without tracing ingress accelerates failure.

3. Ballast Systems and Stability Control

Ballast systems control trim, list, and hull stress.

They operate with large volumes at relatively low pressure, often using dynamic pumps optimised for flow rather than precision.

Ballast misuse introduces risks:

- asymmetric loading

- unintended structural stress

- free surface effects

Incorrect ballast sequencing or valve alignment creates stability issues that develop slowly and manifest suddenly.

Ballast water is also biologically aggressive. Sediment, organisms, and corrosion products degrade tanks and valves internally.

4. Oily Water Separation and Compliance Pressure

Oily water separators are not treatment plants.

They are compliance devices operating within strict limits.

Oily Water Separation, Compliance Limits, and Operational Reality

Oily water separators are not treatment plants.

They are compliance devices, engineered to satisfy a narrowly defined regulatory requirement under controlled conditions that rarely exist in a real engine room.

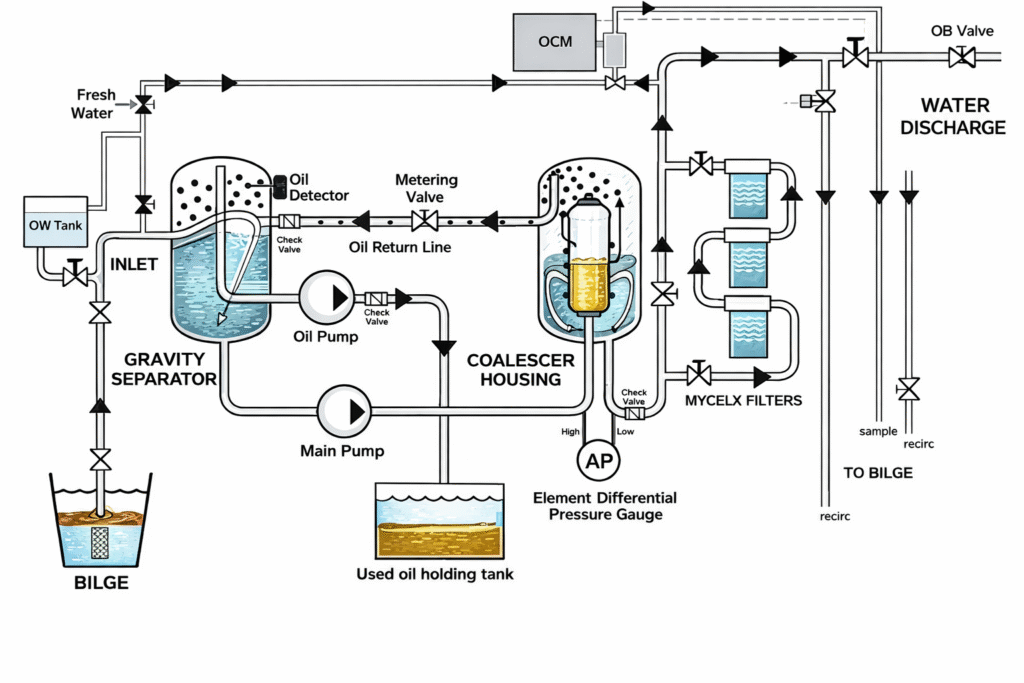

A shipboard oily water separator (OWS) exists for one purpose only: to allow the discharge of machinery space bilge water in a manner that complies with MARPOL 73/78. It is not designed to “clean” bilge water in a general sense, nor to neutralise the full spectrum of contaminants that accumulate in the bilge during normal shipboard operation. It is designed to reduce oil content to within a defined numerical limit under test conditions prescribed by regulation.

Bilge Water Composition and System Assumptions

Bilge water itself is an unavoidable by-product of ship operation. Even on a well-maintained vessel, small but continuous leaks from diesel generators, compressors, pumps, coolers, seals, and pipework introduce oil into spaces where water inevitably accumulates. Added to this are residues from fuel handling, lubrication systems, hydraulic equipment, soot, corrosion products, cleaning agents, and, in practice, traces of almost every fluid carried in the machinery space.

The OWS is expected to deal with this mixture, despite the fact that it was never designed for such chemical complexity.

Modern oily water separators are fitted with oil content monitors (OCMs) and automatic stopping or recirculation arrangements that activate when the measured oil content of the discharge exceeds the regulatory limit, typically 15 parts per million. This figure is not an engineering optimum; it is a legal threshold. Fifteen parts per million represents approximately 15 cubic centimetres of oil in one cubic metre of water — a quantity small enough to demand precise separation under ideal conditions, but large enough to be easily masked by emulsification, detergents, or sensor fouling.

Under MARPOL MEPC 107(49), which governs modern OWS approval, systems must demonstrate the ability to achieve less than 15 ppm even with heavily emulsified oils under laboratory test conditions. These tests are conducted with carefully prepared mixtures, controlled temperatures, stable flow rates, and known oil types. They do not replicate the chaotic composition of real bilge water collected over weeks or months of operation.

Why Real Engine Rooms Defeat Separator Design

In service, the assumptions underlying OWS operation are routinely violated.

Flow is rarely stable. Bilge pumps cycle, tanks are stripped intermittently, and suction conditions vary with ship motion and tank levels. Oil concentration is unpredictable, fluctuating with machinery condition, maintenance activity, and human behaviour. Detergents and cleaning chemicals — often incompatible with separator design — emulsify oil into droplets small enough to bypass gravity and coalescence stages entirely.

When this happens, the separator may still appear to function. Discharge water may look clear. The oil content monitor may read acceptably for a period. But apparent compliance and actual compliance are not the same thing.

Most marine OWS designs begin with some form of gravity separation, allowing free oil to rise and be skimmed into a sludge or waste oil tank. Because gravity separation alone is insufficient to meet discharge limits, additional stages are added. These commonly include filters and coalescer elements designed to break surface tension between oil droplets, encouraging them to merge into larger droplets that can separate under buoyancy forces.

These systems work well when oil is present as discrete droplets. They perform poorly when oil is chemically emulsified or when detergents are present. In such cases, oil droplets remain suspended, pass through coalescers, foul sensing equipment, and give rise to false confidence in separator performance.

Oil Content Monitoring and False Assurance

The oil content monitor itself is not a laboratory instrument. It typically operates by shining light through a sample stream and measuring scattering or absorption caused by oil droplets. Heavy oils, soot, or biological growth can foul the optical path, reducing sensitivity or producing misleading readings. Once fouled, the OCM may require flushing or manual cleaning, during which its reliability is temporarily compromised.

The regulatory requirement that OCMs be tamper-proof and active during all operations is intended to prevent deliberate manipulation, but it does not eliminate the risk of inadvertent misreading caused by contamination or poor maintenance.

From an engineering perspective, the most dangerous belief is that an OWS will “take care of” whatever enters it.

It will not.

It is designed to operate within a narrow envelope: limited flow variation, limited oil concentration, minimal emulsification, and chemically compatible contaminants. Outside that envelope, performance degrades rapidly and often invisibly.

Legal Boundary and Engineering Responsibility

Attempts to bypass, dilute, or manipulate discharge — whether by piping arrangements, procedural shortcuts, or operational sequencing — are not engineering solutions. They are criminal acts under international law, with severe consequences for both vessel and crew. The oil record book exists precisely because oily water management is not trusted to be self-policing.

Every transfer, discharge, or internal movement of oily residues must be recorded accurately and contemporaneously. These records are not paperwork exercises; they are legal documents scrutinised in the aftermath of incidents and inspections. Discrepancies between recorded operations and system capability are often the first indicators of deeper problems.

The fundamental truth is that oily water separators are not forgiving systems. They sit at the boundary between engineering and law. They do not tolerate ambiguity, improvisation, or wishful thinking.

A separator that “usually passes” is not compliant.

A discharge that “looks clean” is not necessarily legal.

And a system that has not been challenged under realistic conditions is unproven.

Engineering discipline, honest operation, and respect for the limits of the equipment are the only sustainable way to operate oily water systems — because when they fail, the consequences extend far beyond the engine room.

5. Sensors, Automation, and False Confidence

Bilge and OWS systems rely heavily on sensors: level switches, oil content meters, valve feedback.

Sensor drift is common. Fouling is routine. Calibration is often deferred.

Automation gives the illusion of control. A “normal” display does not mean the system is functioning correctly.

Local inspection often contradicts the control room.

6. Operational Practices and Degradation Paths

Routine practices drive degradation:

- washing oil into bilges

- using detergents not compatible with separators

- deferring tank cleaning

- ignoring small leaks

These practices accumulate risk invisibly.

Compliance pressure often encourages short-term thinking that creates long-term vulnerability.

7. Failure Development and Damage Progression

Failures develop through:

- leakage accumulation

- sensor masking

- pump or valve degradation

- loss of control or discharge capability

- flooding or pollution incident

The final event appears sudden. It is not.

8. Human Oversight and Engineering Judgement

Engineers protect these systems by:

- tracing water sources, not just pumping them

- maintaining separator honesty

- understanding regulatory intent

Judgement determines whether these systems protect the ship or end its voyage.

Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Failure propagates into:

- machinery flooding

- electrical loss

- structural stress

- regulatory detention

Bilge and ballast systems are defensive systems. When they fail, escalation is rapid.