Last-Resort Energy, False Confidence, and the Boundary Between Survival and Compliance

ENGINE ROOM → Auxiliary & Support Systems

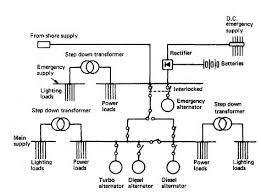

System Group: Emergency Electrical Supply

Primary Role: Supply of essential services following main power failure

Interfaces: Emergency Switchboard · Essential Consumers · Fire Safety · Steering

Operational Criticality: Safety-Critical

Failure Consequence: Loss of statutory systems → loss of control → regulatory and safety escalation

Emergency power is not a backup convenience.

It is a legal minimum for survival.

Position in the Plant

The emergency power system exists outside normal operation. It remains idle, untested under load, and often forgotten — until the moment it is needed absolutely.

From an engineering standpoint, emergency power systems are paradoxical:

- they must work instantly

- they operate infrequently

- they are often poorly understood

Their success is measured not by efficiency, but by availability under worst conditions.

Contents

System Purpose and Design Intent

Emergency Generator Architecture

Starting, Transfer, and Blackout Recovery

Load Prioritisation and Essential Services

Fuel, Cooling, and Environmental Vulnerability

Failure Development and Hidden Weaknesses

Human Oversight and Emergency Reality

1. System Purpose and Design Intent

Emergency power systems exist to meet SOLAS intent, not operational comfort.

They supply power to:

- emergency lighting

- communication systems

- fire pumps

- steering gear (limited)

- alarms and navigation equipment

They are not designed to support full ship operation.

Confusing emergency capability with operational resilience is a dangerous assumption.

2. Emergency Generator Architecture

Emergency generators are physically segregated from main machinery spaces.

They rely on:

- independent fuel supply

- independent cooling arrangements

- independent starting systems

This separation improves survivability, but introduces isolation risk. Faults may go unnoticed for long periods.

Emergency generators often operate cold, increasing starting stress and mechanical wear.

3. Starting, Transfer, and Blackout Recovery

Emergency power must start automatically following loss of main power.

Delays longer than statutory limits compromise safety and compliance.

Common vulnerabilities include:

- flat starting batteries

- fuel degradation

- air ingress

- control logic failure

Automatic transfer systems must function flawlessly under stress. Manual intervention is a last resort, not a plan.

4. Load Prioritisation and Essential Services

Emergency switchboards are designed around load shedding by design, not control.

Only essential consumers are connected.

Adding non-essential loads, even temporarily, undermines the entire system. Emergency power plants have minimal overload tolerance.

A system that “usually copes” is not compliant.

5. Fuel, Cooling, and Environmental Vulnerability

Emergency generators often use small fuel tanks vulnerable to:

- contamination

- microbial growth

- long-term stagnation

Cooling systems may rely on air or simplified water circuits with limited margin.

Environmental exposure — heat, humidity, vibration — degrades emergency systems silently.

6. Failure Development and Hidden Weaknesses

Emergency power failures often stem from:

- lack of testing under real load

- deferred maintenance

- assumption-based confidence

Systems that pass routine checks may fail when actually demanded.

7. Human Oversight and Emergency Reality

Engineers protect emergency power systems by:

- exercising them realistically

- verifying load acceptance

- maintaining starting systems rigorously

An emergency generator that has never carried real load is unproven.

Compliance does not equal readiness.

Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Emergency power directly affects:

- fire response

- steering survivability

- crew safety

- regulatory standing

When emergency power fails, escalation is immediate and unforgiving.