Thermal Stability, Control Circuits, and Operational Integrity Across Marine Plants

System Group: Cooling & Heat Transfer

Primary Role: Maintenance of controlled thermal conditions across machinery, fluids, gases, structures, and human spaces

Applies To: Merchant Ships · Offshore Platforms & Rigs · Mega Yachts · Naval & Special Vessels

Interfaces: HT/LT Cooling · Oil & Fuel Systems · Heat Exchangers · HVAC · Refrigeration · Electrical Systems · Automation

Operational Criticality: Continuous

Failure Consequence: Loss of thermal margin → accelerated wear → system instability → safety risk or shutdown

Temperature control is not a discrete subsystem.

It is the governing discipline that determines whether every other system on board can operate within survivable limits.

Contents

- System Purpose and Design Intent

- Temperature as a Dominant Control Variable

- Boundaries, Interfaces, and Separation Philosophy

- Temperature Control Architecture Across Marine Sectors

4.1 Merchant Ships

4.2 Offshore Platforms and Rigs

4.3 Mega Yachts and High-Comfort Vessels - Major Temperature Control Circuits

5.1 Engine Structural Temperature Control

5.2 Fluid Temperature Control (Oil, Fuel, Water)

5.3 Gas and Air Temperature Control

5.4 Electrical and Power Electronics Temperature Control

5.5 Human Space and Process Temperature Control - Control Devices, Actuators, and Regulation Philosophy

- Control Under Real Operating Conditions

- Degradation, Drift, and Loss of Control Margin

- Human Oversight, Watchkeeping, and Engineering Judgement

- Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

1. System Purpose and Design Intent

Temperature control exists to govern material behaviour over time.

Every component on board — metal, oil, fuel, insulation, electronics, seals — exists within a thermal envelope beyond which degradation accelerates rapidly. Exceeding these limits does not always cause immediate failure. Instead, it shortens life invisibly.

The purpose of temperature control is therefore not to avoid alarms, but to slow damage accumulation.

Unlike pressure or speed, temperature:

- stores energy

- changes slowly

- masks instability

- continues damaging components even after the initiating cause is removed

A plant that “looks stable” may already be operating without thermal margin.

2. Temperature as a Dominant Control Variable

Temperature is not merely an operating parameter — it is a multiplier of failure mechanisms.

Small temperature increases accelerate:

- corrosion rates

- oil oxidation

- fuel degradation

- insulation breakdown

- seal hardening

- metal fatigue

Equally dangerous are temperature gradients. Uneven heating or cooling produces differential expansion, which leads to:

- liner distortion

- gasket movement

- cracking

- loss of alignment

Effective temperature control therefore focuses on:

- uniformity

- rate of change

- margin

Not on single numerical targets.

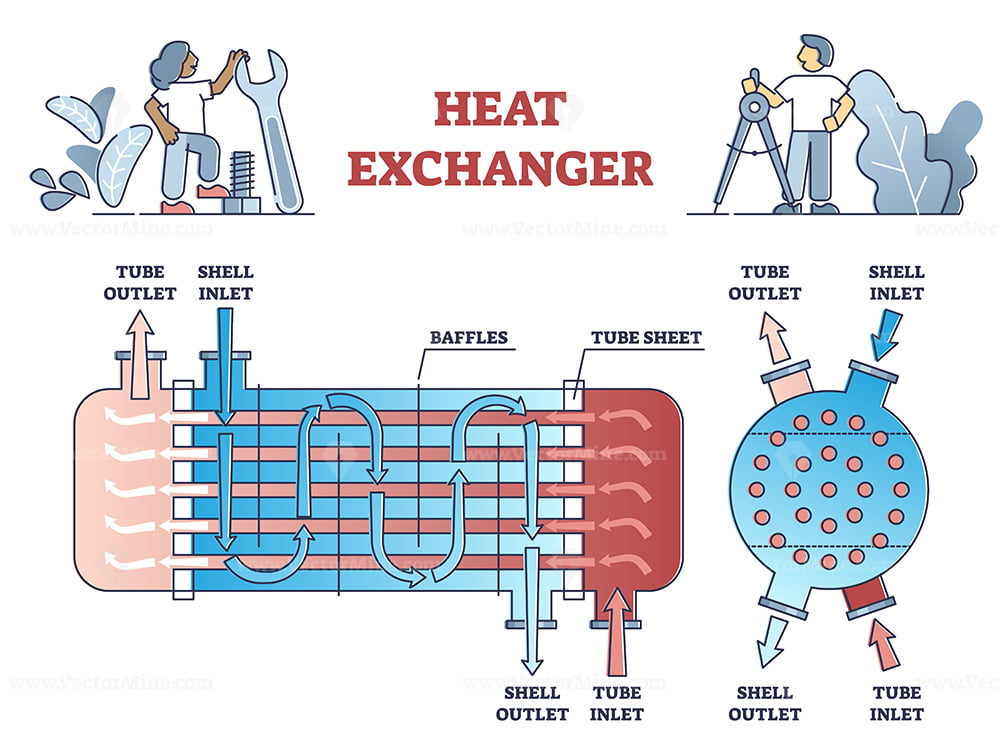

3. Boundaries, Interfaces, and Separation Philosophy

Temperature control systems exist to decouple competing requirements.

Examples:

- Engines require hot metal; oil requires controlled cooling

- Fuel requires heating; injectors require cooling

- Power electronics require cooling; accommodation requires heating

- Humans require comfort; machinery rejects waste heat

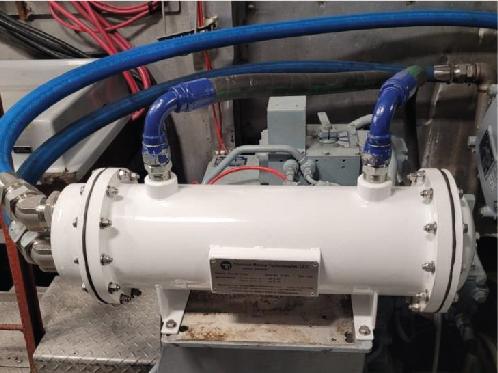

Separation is achieved using:

- dedicated circuits

- heat exchangers

- bypass and mixing logic

- independent control loops

Any attempt to merge circuits for “simplicity” transfers instability from one system into another.

Temperature control complexity is not poor design — it is damage prevention.

4. Temperature Control Architecture Across Marine Sectors

4.1 Merchant Ships

On merchant vessels, temperature control prioritises:

- machinery protection

- fuel efficiency

- long-term availability

Systems include:

- HT/LT freshwater temperature control

- oil and fuel cooling

- charge air cooling

- accommodation HVAC

- refrigerated spaces

Control philosophy is conservative and tolerant of degradation. Stability is preferred over rapid response.

4.2 Offshore Platforms and Rigs

On offshore installations, temperature control becomes process-critical.

Additional controlled systems include:

- gas processing trains

- hydrate prevention circuits

- chemical injection temperature control

- explosion-risk mitigation systems

Control circuits are:

- redundant

- tightly interlocked

- continuously monitored

Loss of temperature control often mandates full process shutdown.

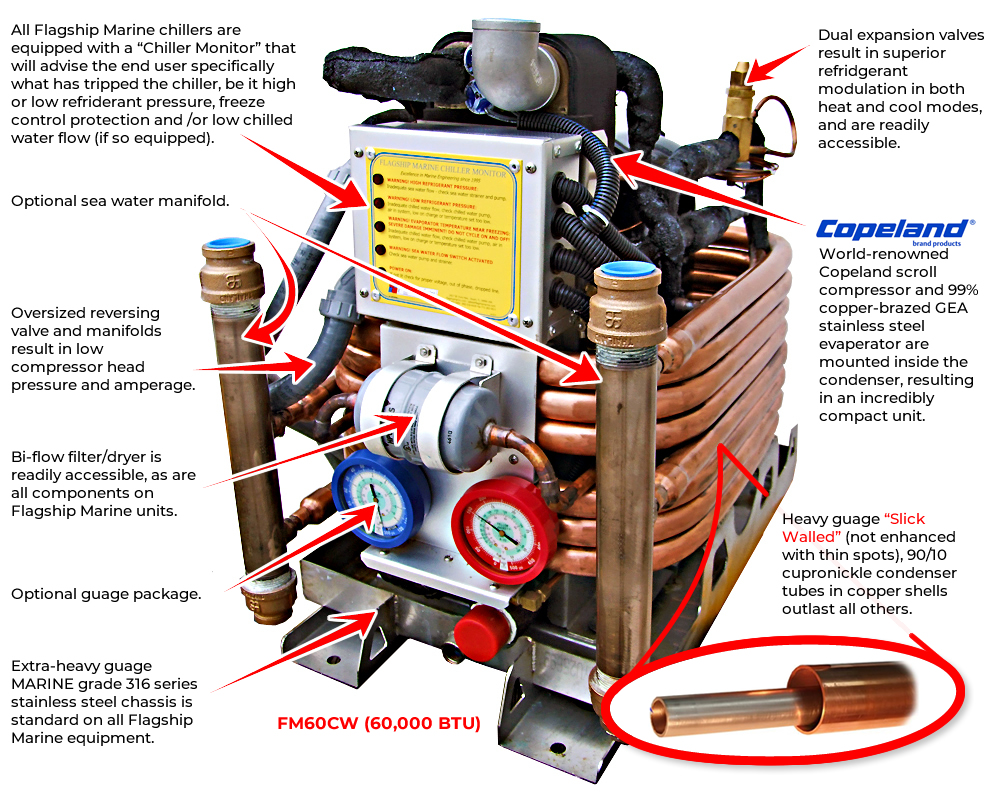

4.3 Mega Yachts and High-Comfort Vessels

On mega yachts, temperature control extends beyond machinery into:

- comfort zoning

- noise and vibration reduction

- aesthetic constraints

Systems are highly automated, often complex, and less tolerant of drift. Failure consequences may appear cosmetic, but machinery risk remains unchanged.

5. Major Temperature Control Circuits

5.1 Engine Structural Temperature Control

Protects:

- cylinder liners

- heads

- exhaust components

- blocks

Implemented via:

- HT freshwater circuits

- three-way mixing valves

- bypass logic

- jacket water heaters

The objective is metal temperature stability, not maximum cooling.

5.2 Fluid Temperature Control (Oil, Fuel, Water)

Maintains:

- oil viscosity

- fuel density

- injection accuracy

Circuits include:

- oil coolers with bypass

- fuel heaters and coolers

- mixing loops for fine regulation

Over-cooling is a dominant low-load failure mode.

5.3 Gas and Air Temperature Control

Controls:

- charge air density

- condensation risk

- combustion efficiency

Includes:

- charge air coolers

- intake air heaters

- exhaust gas temperature control for WHR

These systems must respond quickly without destabilising upstream flow.

5.4 Electrical and Power Electronics Temperature Control

Modern vessels rely on:

- VFDs

- converters

- inverters

- battery systems

Cooling methods include:

- air cooling

- liquid cooling

- chilled water loops

Electrical temperature failures are sudden and unforgiving.

5.5 Human Space and Process Temperature Control

Accommodation HVAC, galleys, refrigerated spaces, and process rooms compete thermally with machinery systems.

When margin is lost, human comfort is usually sacrificed first — often masking deeper plant instability.

6. Control Devices, Actuators, and Regulation Philosophy

Temperature is controlled indirectly using:

- mixing valves

- bypass valves

- staged heat rejection

- variable flow

Stable control prioritises:

- slow response

- limited valve travel

- avoidance of hunting

Fast control often creates oscillation rather than precision.

7. Control Under Real Operating Conditions

Design conditions are rare.

Real plants operate with:

- fouled exchangers

- drifting sensors

- altered flow paths

- partial load

The most dangerous condition is apparent stability with exhausted margin.

8. Degradation, Drift, and Loss of Control Margin

Temperature control systems degrade through:

- fouling

- valve wear

- actuator fatigue

- sensor drift

Control authority erodes quietly until sudden instability appears.

9. Human Oversight, Watchkeeping, and Engineering Judgement

Automation regulates numbers. Engineers interpret behaviour.

Experienced watchkeepers recognise:

- excessive valve movement

- delayed stabilisation

- unexplained trend shifts

- increasing manual intervention

Judgement prevents damage long before alarms trigger.

10. Relationship to Adjacent Systems and Cascading Effects

Loss of temperature control destabilises:

- lubrication systems

- fuel injection

- electrical systems

- HVAC and refrigeration

- process stability offshore

Because temperature governs material behaviour, its loss undermines every system simultaneously.