Principles, Systems, Sequences, Safeties, and Practical Engine-Room Reality

Meta Description: A complete marine engineering guide to starting and reversing ship engines: air start systems, control logic, interlocks, slow-turning, reversing methods for two-stroke, four-stroke, diesel-electric, and hybrid propulsion.

Tags: engine starting, reversing, air start system, starting air, manoeuvring, bridge control, engine safety, turning gear, slow turning, ahead astern

Introduction

Starting and reversing are the most safety-critical transient operations any marine propulsion system performs.

At sea, engines spend most of their life running steadily.

But starting, stopping, and reversing occur:

- In confined waters

- Close to hazards

- Under time pressure

- Often with cold machinery

- Frequently with non-ideal loads

This is why starting and reversing systems are heavily interlocked, sequenced, and protected — and why engineers must understand what happens, not just which button to press.

This page is the single reference point for:

- How marine engines are started

- How direction is changed

- Why systems are designed the way they are

- What commonly goes wrong

- How different engine types handle the same task differently

Contents

- 1. Why Starting & Reversing Matter

- 2. Core Principles (Common to All Engines)

- 3. Starting Systems Overview

- 4. Starting Air Systems (Deep Dive)

- 5. Two-Stroke Engine Starting & Reversing

- 6. Four-Stroke Engine Starting & Reversing

- 7. Diesel-Electric & Hybrid Starting Logic

- 8. Bridge Control, ECR Control & Local Control

- 9. Safeties, Interlocks & Permissives

- 10. Typical Faults & Troubleshooting Patterns

- 11. Operational Best Practice at Sea

- 12. Common Misconceptions

- 13. How This Links to Other ENGINE Topics

1) Why Starting & Reversing Matter

From an engineering perspective, starting and reversing are transient states — and transients create stress.

During these moments:

- Lubrication is not fully established

- Clearances are changing rapidly

- Combustion quality is unstable

- Load may be applied suddenly

- Human reaction time matters

Most serious engine damage incidents occur:

- Immediately after start

- During manoeuvring

- During crash stops or repeated reversals

That’s why marine engines use compressed air, sequenced fuel admission, slow-turning, and multiple layers of interlocks.

2) Core Principles (Common to All Marine Engines)

Regardless of engine type, every marine starting system must achieve four things:

- Rotate the engine from rest

- Establish lubrication before firing

- Introduce fuel at the correct moment

- Allow controlled acceleration to idle

Reversing adds a fifth requirement:

- Change torque direction without mechanical damage

This is achieved differently depending on engine design — but the principles never change.

3) Starting Systems Overview

Main starting methods used at sea

- Compressed air starting (large engines)

- Electric motor starting (small/medium engines)

- Hydraulic starting (specialist applications)

For main propulsion engines, compressed air remains dominant because:

- It delivers very high torque instantly

- It does not rely on electrical power during blackout

- It allows repeated starts in short succession

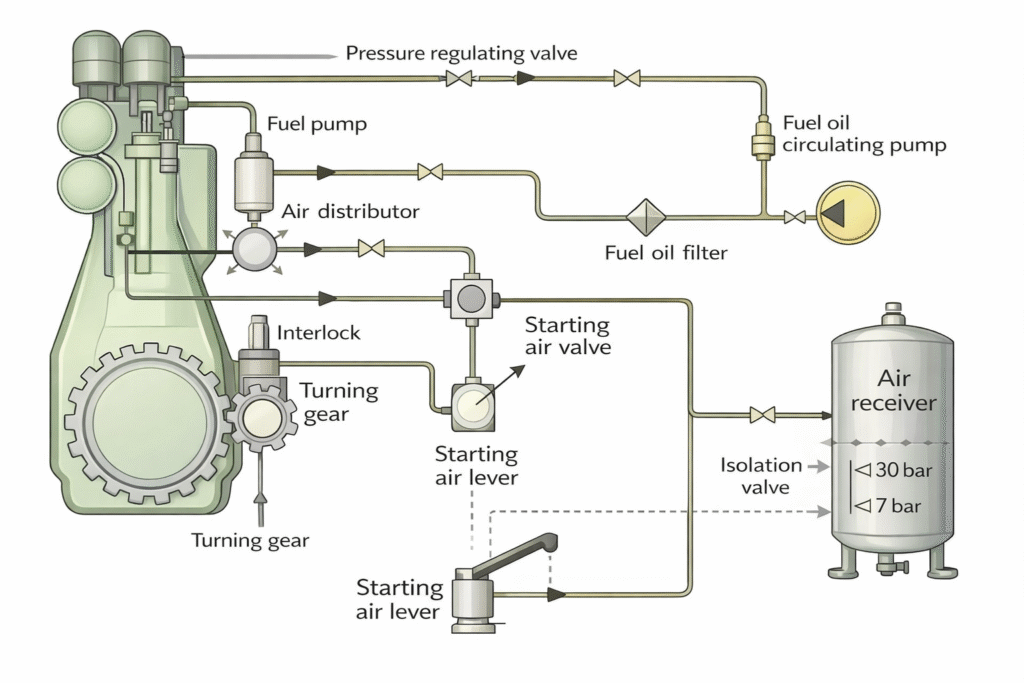

4) Starting Air Systems

4.1 System components

A typical starting air system consists of:

- Air compressors

- Starting air receivers (bottles)

- Non-return valves

- Starting air distributor

- Cylinder starting air valves

- Control air system

- Flame arrestors and relief devices

4.2 Why air is used instead of fuel

Fuel ignition requires:

- Adequate compression temperature

- Correct injection timing

- Stable rotational speed

Compressed air:

- Spins the engine regardless of temperature

- Clears cylinders of residual gases

- Ensures oil pressure builds before firing

4.3 Air admission sequence

Air is admitted:

- In the direction of intended rotation

- To cylinders near TDC

- In a timed sequence controlled by the distributor

Once the engine reaches firing speed:

- Starting air cuts off

- Fuel is admitted

- Engine becomes self-sustaining

5) Two-Stroke Engine Starting & Reversing

5.1 Two-stroke starting sequence

- Turning gear disengaged

- Pre-lube complete

- Indicator cocks open (initial start)

- Start command given

- Starting air distributor aligns

- Air admitted to selected cylinders

- Engine rotates to firing speed

- Fuel admitted

- Air cut-off

- Engine stabilises at manoeuvring RPM

5.2 Reversing a two-stroke engine

Reversing is achieved by changing valve and fuel timing, not by reversing a gearbox.

Key actions:

- Exhaust valve timing shifts

- Fuel injection timing shifts

- Starting air distributor switches to opposite direction

The engine is effectively re-timed to run backwards.

This is why two-stroke engines:

- Can reverse without gearboxes

- Are ideal for large slow-speed propulsion

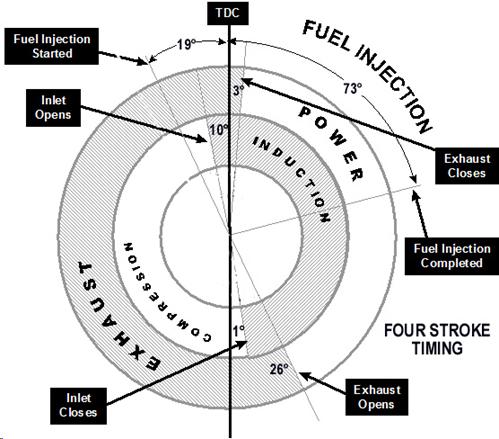

6) Four-Stroke Engine Starting & Reversing

6.1 Four-stroke starting

Four-stroke engines typically:

- Start using electric or air-assisted systems

- Fire at much lower torque than two-strokes

- Reach idle speed rapidly

6.2 Reversing in four-stroke systems

Four-stroke engines do not reverse direction internally.

Reversing is achieved by:

- Reversible gearboxes

- Controllable Pitch Propellers (CPP)

Engine direction remains constant.

This simplifies engine design but:

- Adds mechanical complexity elsewhere

- Introduces gearbox and pitch control systems

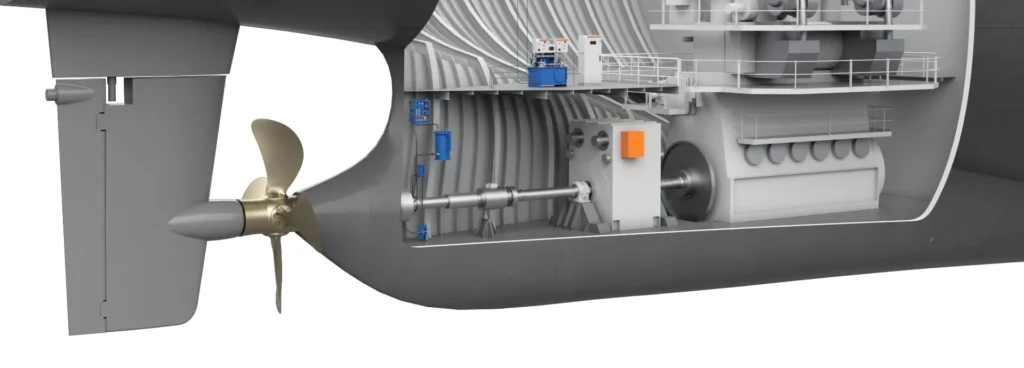

7) Diesel-Electric & Hybrid Starting Logic

7.1 Diesel-electric propulsion

There is no engine reversing.

Process:

- Gensets start and synchronise

- Electrical power supplied to propulsion motors

- Motor direction is controlled electrically

Reversing is:

- Instant

- Smooth

- Limited by motor and drive protection

7.2 Hybrid systems

Hybrid systems add complexity:

- Engine start logic

- Battery SOC limits

- Mode selection (electric / mechanical / combined)

Reversing logic must coordinate:

- Propulsion motor direction

- Shaft line torque

- Engine clutch or PTI/PTO status

8) Bridge Control, ECR Control & Local Control

Control hierarchy

- Local control – direct engine control (maintenance/emergency)

- ECR control – normal manoeuvring authority

- Bridge control – navigational command

Only one station may have control at a time.

Transfer of control requires:

- RPM at zero

- Confirmation of command

- Interlock satisfaction

9) Safeties, Interlocks & Permissives

Common start permissives

- Turning gear disengaged

- Adequate starting air pressure

- Lube oil pressure available

- No critical alarms active

- Correct control station selected

Common reverse protections

- RPM below limit

- Fuel cut-off before direction change

- Pitch at zero (CPP systems)

These systems exist to protect machinery from human error.

10) Typical Faults & Troubleshooting Patterns

Engine does not start

- No starting air pressure

- Distributor not shifting

- Turning gear interlock active

- Control air failure

Engine starts then dies

- Fuel admission failure

- Incorrect timing

- Low lube oil pressure trip

Reversing failure

- Distributor stuck

- Control air leak

- CPP feedback mismatch

11) Operational Best Practice at Sea

Good engineers:

- Avoid repeated crash starts

- Allow stabilisation between reversals

- Monitor air consumption

- Respect warm-up requirements

- Understand automation — not fight it

12) Common Misconceptions

❌ “Starting air is only for emergencies”

✔ It is the primary starting method for large engines

❌ “Electric ships don’t need starting procedures”

✔ They still rely on PMS logic and protection sequencing

❌ “Reversing is instant”

✔ Only if systems are healthy and limits are respected

13) How This Links to Other ENGINE Topics

This page connects directly to:

- Two-Stroke Engines → air start & reversing timing

- Four-Stroke Engines → CPP & gearbox operation

- Hybrid/Electric Propulsion → motor direction control

- Control & Automation → PMS, interlocks, safety logic

- Faults & Troubleshooting → start failures, manoeuvring alarms

It is a core foundation page for the entire ENGINE section.